Static Fields: Fall-2025

HW 10 (SOLUTION): Due W5 D5

- Ampere's Law for a Cylinder

S1 5309S

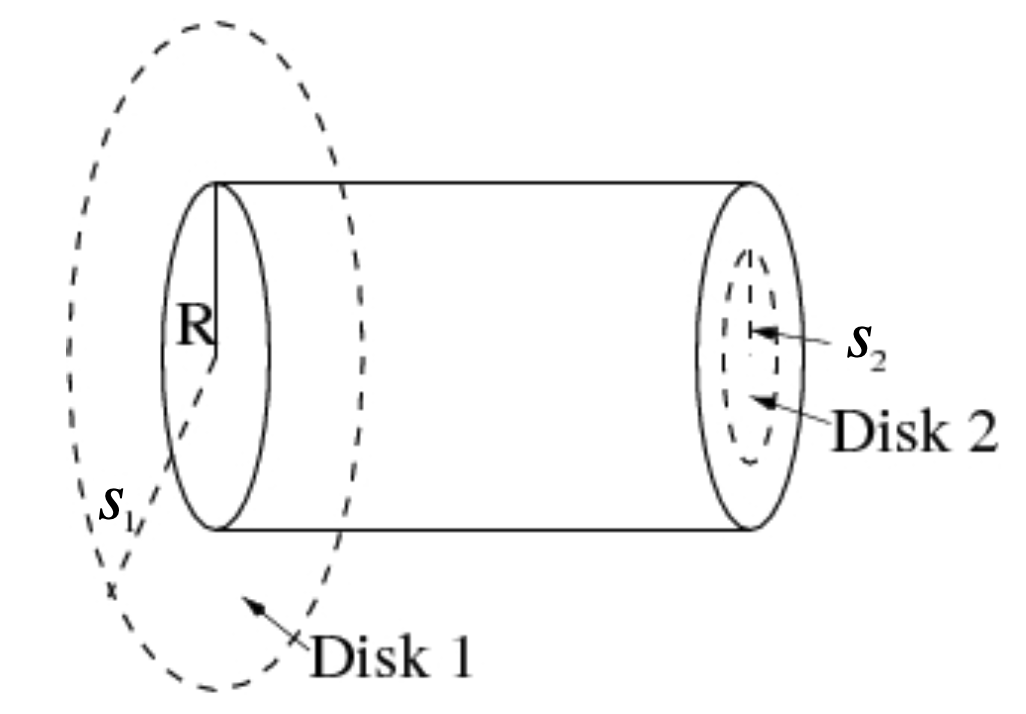

In this problem, you will be investigating a cylindrical wire of finite radius \(R\), carrying

a non-uniform current density \(J=\kappa s \;\hat{z}\), where \(\kappa\) is a

constant and \(s\) is the distance from the axis of the cylinder.

-

Find the total current flowing through the wire.

The differential area element of a cross section of the wire is: \[ \vec{A} = (ds \, \hat{s} + s \, d\phi \, \hat\phi) = s\,ds\,d\phi\,\hat{s}\] \begin{align*} I_{enc} &= \int \vec{J} \cdot d\vec{A}\\ &= \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^R(\kappa r \hat{z})\cdot \hat{z} \, r\, dr\, d\phi\\ &= \frac{2\pi\kappa R^3}{3} \end{align*}

-

Find the current flowing through Disk 2, a central (circular

cross-section) portion of the wire out to a radius \(s_2<R\).

\begin{align*} I_{enc} &= \int \vec{J} \cdot d\vec{A}\\ &= \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{s_2}(\kappa s \hat{z})\cdot \hat{z}\, s\, ds\, d\phi\\ &= {2\pi\kappa s_2^3\over 3} \end{align*}

-

Use Ampere's law to find the magnetic field at a

distance \(s_1\) outside the wire.

\(\vec{B}\) must point in the \(\hat{\phi}\) direction. How do we know this? The right-hand rule in the Biot-Savart law shows that \(\vec{B}\) must be perpendicular to the current, so it cannot have a component in the \(z\)-direction. Suppose \(\vec{B}\) had a component in the \(\hat{s}\)-direction. If we reversed the current, it would have a component in the \(-\hat{r}\) direction. If we then turned the wire over (flipping it end-to-end), this flip would not change the direction of the field. After both changes, we would be back to the original configuration, but the direction of the field would have switched. This is not possible. Symmetry also shows that \(\vec{B}\) is a function only of \(r\). How do we know this? Suppose B depended on \(\phi\) or \(z\), then if we rotated the wire or moved it along its axis, then the field would change, but neither of these is a change that we could detect in the wire. Therefore, \(\vec{B}= B(r)\,\hat{\phi}\). Ampere's law is:

\begin{align*} \mu_0 I_{enc} &= \oint \vec{B} \cdot d\hat{r}\\ &= \int B(s_1) \,\hat{\phi} \cdot r_1 \, d\phi \,\hat{\phi}\\ &= 2\pi B(s_1) \,s_1 \end{align*} Using the result from part (a) and solving for B(s), we find \begin{equation*} \vec{B}(s_1)=\frac{\mu_0\kappa R^3}{3 s_1}\, \hat{\phi} \end{equation*}

Use Ampere's law to find the magnetic field at a distance \(s_2\) inside the wire.

The calculation is the same as in part (c), but using the result from part (b) for the current enclosed. \begin{align*} \mu_0 I_{enc} &= \int \vec{B} \cdot d\vec{r}\\ &= \int B(s_2) \,\hat{\phi} \cdot s_2 \, d\phi \,\hat{\phi}\\ &= 2\pi B(s_2) \,s_2 \end{align*} so that \begin{equation*} \vec{B}(s)=\frac{\mu_0\kappa s^2}{3}\, \hat{\phi} \end{equation*}

-

Find the total current flowing through the wire.

- Magnetic Field and Current

S1 5309S

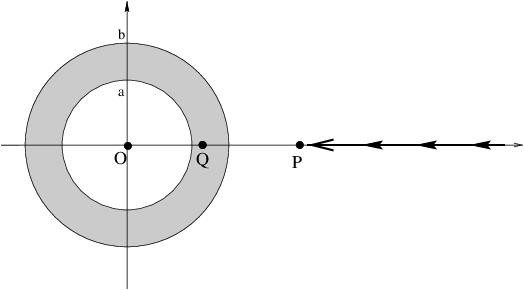

Consider the magnetic field

\[

\vec{B}(s,\phi,z)=

\begin{cases}

0&0\le s<a\\

\alpha \frac{1}{s}(s^4-a^4)\, \hat{\phi}&a<s<b\\

0&s>b

\end{cases}

\]

- Use step and/or delta functions to write this magnetic field as a single

expression valid everywhere in space.

We need to turn the field on at \(s=a\) and off at \(s=b\): \[ \vec{B}(s,\phi,z)=\alpha \frac{1}{s}(s^4-a^4)\left[\Theta(s-a)-\Theta(s-b)\right]\, \hat{\phi} \]

- Find a formula for the current density that creates this magnetic field.

Use Maxwell's equation for current density and calculate the curl in cylindrical coordinates. Don't forget to include the step functions and use the product rule! \begin{align} \vec{J}(\vec{r})&=\frac{1}{\mu_0}\vec{\nabla}\times \vec{B}\\ &=\frac{1}{\mu_0} \frac{1}{s}\frac{\partial}{\partial s}\left(s {B}_{\phi}\right)\\ &=\frac{1}{\mu_0} \frac{1}{s}\frac{\partial}{\partial s} \left(\alpha (s^4-a^4)\left[\Theta(s-a)-\Theta(s-b)\right]\right)\, \hat{z}\\ &=\frac{\alpha}{\mu_0} \frac{1}{s}\left(4s^3\left[\Theta(s-a)-\Theta(s-b)\right] +(s^4-a^4)\left[\cancel{\delta(s-a)}-\delta(s-b)\right]\right)\, \hat{z}\\ \end{align} The delta function at \(s=a\) does not contribute since the coefficient of that term \(s^4-a^4\) is zero at \(s=a\).

- Interpret your formula for the current density, i.e. explain briefly in words where the

current is.

There is a volume current density with magnitude \(\frac{4\alpha}{\mu_0} s^2\) flowing up the cylinder. The total current due to this current density is the flux through a horizontal plane: \begin{align} I_{\text{total}}&=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_a^b \frac{4\alpha}{\mu_0} s^2\hat{z}\cdot s\, ds\, d{\phi}\hat{z}\\ &=\frac{8\pi\alpha}{\mu_0}\int_a^b s^3\, ds\\ &=\frac{2\pi\alpha}{\mu_0}(b^4-a^4) \end{align} There is also a surface current density which is described as a volume current density with a delta function at \(s=b\) with magnitude \(\frac{\alpha}{\mu_0} \frac{s^4-a^4}{s}\) flowing down the cylinder. The total current due to this current density is the flux through a horizontal plane: \begin{align} I_{\text{total}}&=-\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{\infty} \frac{\alpha}{\mu_0} \frac{s^4-a^4}{s}\delta(s-b)\hat{z}\cdot s\, ds\, d{\phi}\hat{z}\\ &=\frac{2\pi\alpha}{\mu_0}\int_0^{\infty} (s^4-a^4)\delta(s-b)\, ds\\ &=\frac{2\pi\alpha}{\mu_0}(b^4-a^4) \end{align} These two total currents are equal in magnitude and opposite in direction, so Ampère's Law tells us that the magnetic field for \(s>b\) is zero, which we see in the original statement of the problem.

- Use step and/or delta functions to write this magnetic field as a single

expression valid everywhere in space.

- Path Independence

S1 5309S

The gravitational field due to a spherical shell of mass is given by: \begin{equation} \vec g =\begin{cases} 0&r<a\\ -\frac{4}{3}\pi\rho\,G\left({r}-\frac{a^3}{r^2}\right)\hat{r}&a<r<b\\ -\frac{4}{3}\pi\rho\, G\left(\frac{b^3-a^3}{r^2}\right)\hat{r}&b<r\\ \end{cases} \end{equation} where \(a\) is the inside radius of the shell, \(b\) is the outside radius of the shell, and \(\rho\) is the constant mass density.

-

Using an explicit line integral, calculate the work required to

bring a test mass, of mass \(m_0\), from infinity to a point \(P\),

which is a distance \(c\) (where \(c>b\)) from the center of the shell.

\begin{align} \int_{\infty}^P \vec F\cdot \vec{dl} &= \int_{\infty}^c \frac{GMm_0}{r^2}\hat r \cdot dr\, \hat r\\ &= \left. -\frac{GMm_0}{r}\right|_{\infty}^c\\ &= -\frac{GMm_0}{c} \end{align} where I have used \begin{equation} M=\frac{4}{3} \pi\rho(b^3-a^3). \end{equation}

Warning: Watch the signs! The force I exert bringing the mass in from infinity is outward pointing.

Notice that the work done is just \(m_0\) times the value of the potential.

-

Using an explicit line integral, calculate the work required to

bring the test mass along the same path, from infinity to the point

\(Q\) a distance \(d\) (where \(a<d<b\)) from the center of the shell.

\begin{align} \int_{\infty}^Q \vec F\cdot \vec{dl} &= \int_{\infty}^b \frac{GMm_0}{r^2}\hat r \cdot dr\, \hat r +\int_b^d \frac{4\pi\rho Gm_0}{3}\left(r-\frac{b^3}{r^2}\right)\hat r \cdot dr\, \hat r\\ &= \left. -\frac{GMm_0}{r}\right|_{\infty}^b +\left. \frac{4\pi\rho Gm_0}{3} \left(\frac{r^2}{2}+\frac{b^3}{r}\right)\right|_b^d\\ &= -\frac{GMm_0}{b}+\frac{4\pi\rho Gm_0}{3} \left(\frac{d^2}{2}+\frac{a^3}{d}-\frac{b^2}{2}-\frac{a^3}{b}\right)\\ &= -4\pi\rho Gm_0\left(\frac{b^2}{2}-\frac{a^3}{3d}-\frac{d^2}{6}\right) \end{align} Notice that the work done is just \(m_0\) times the value of the potential.

-

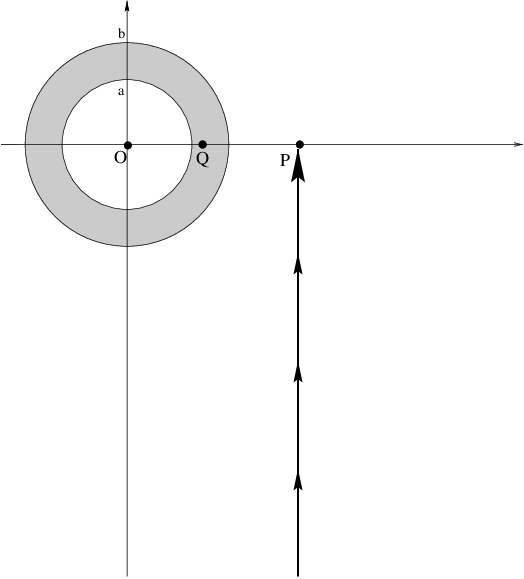

Using an explicit line integral, calculate the work required to

bring the test mass along the same radial path from infinity all the

way to the center of the shell.

\begin{align} \int_{\infty}^0 \vec F\cdot \vec{dl} &= \int_{\infty}^b \frac{GMm_0}{r^2}\hat r \cdot dr\, \hat r -\int_b^a \frac{4\pi\rho Gm_0}{3}\left(\frac{a^3}{r^2}-r\right)\hat r \cdot dr\, \hat r +\int_a^0 0dr\\ &= \left. -\frac{GMm_0}{r}\right|_{\infty}^b -\left. \frac{4\pi\rho Gm_0}{3} \left(-\frac{a^3}{r}-\frac{r^2}{2}\right)\right|_b^a\\ &= -\frac{GMm_0}{b}-\frac{4\pi\rho Gm_0}{3} \left(-\frac{a^3}{a}-\frac{a^2}{2}+\frac{a^3}{b}+\frac{b^2}{2}\right)\\ &= -2\pi\rho Gm_0\left({a^2-b^2}\right) \end{align} where in the last equality I have used \(M=\frac{4}{2} \pi\rho(b^3-a^3)\).

Notice that the work done is just \(m_0\) times the value of the potential.

-

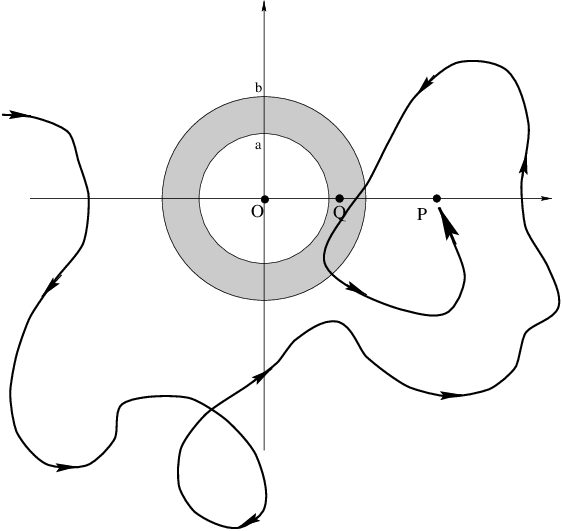

Using an explicit line integral, calculate the work required to

bring in the test mass along the path drawn below, to the point \(P\)

of the first question. Compare the work to your answer from the first question.

I will use spherical coordinates with this diagram in the equatorial plane \(\theta=\frac{\pi}{2}\), with the x-axis pointing downward. Other orientations of spherical coordinates are also ok. If you use cylindrical coordinates, you will get the right answer, but only by accident.

In my version of spherical coordinates, along this path, I have \(\sin\phi=\frac{c}{r}\). Therefore, \(\cos\phi \, d\phi=-\frac{c}{r^2}\, dr\) or \(r\, d\phi=-\frac{c}{\sqrt{r^2-c^2}}\, dr\). Plugging in: \begin{equation} \vec{dl}=dr \hat r + r d\phi \hat \phi =dr \hat r-\frac{c}{\sqrt{r^2-c^2}}\, dr\, \hat\phi \end{equation} \begin{align} \int_{\infty}^P \vec F\cdot \vec{dl} &= \int_{\infty}^c \frac{GMm_0}{r^2}\hat r \cdot \left(dr \hat r-\frac{c}{\sqrt{r^2-c^2}}\, dr\, \hat\phi\right)\\ &= \left. -\frac{GMm_0}{r}\right|_{\infty}^c\\ &= -\frac{GMm_0}{c} \end{align} Notice that the \(\hat\phi\) component of \(\vec{dl}\) does not contribute to the integral. Therefore, I never actually had to calculate how \(\vec{dl}\) depends on \(\phi\). You can see here how the mathematics is forcing the integral to be path independent!

-

What is the work required to bring the test mass from infinity along

the path drawn below to the point \(P\) of question a. Explain your

reasoning.

The work is independent of path. Therefore, the answer to this problem is the same as the answer to part a.

-

Using an explicit line integral, calculate the work required to

bring a test mass, of mass \(m_0\), from infinity to a point \(P\),

which is a distance \(c\) (where \(c>b\)) from the center of the shell.