Static Fields: Fall-2025

HW 09 (SOLUTION): Due W5 D3

- Current in a Wire

S1 5307S

The current density in a cylindrical wire of radius \(R\) is given by

\(\vec{J}(\vec{r})=\alpha s^3\cos^2\phi\,\hat{z}\). Find the total current in the wire.

The total current in the wire is the flux of the current density through an appropriate cross section of the wire. In this case, we will take a circular disk of radius \(R\) in the \(x,y\)-plane. \begin{align} I_{\text{Total}}&=\int \vec{J}\cdot d\vec{A}\\ &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^R(\alpha s^3\cos^2\phi\,\hat{z}) \cdot s\, ds\, d\phi\, \hat{z}\\ &=\alpha\int_0^{2\pi}\cos^2\phi\, d\phi\int_0^R s^4\, ds\\ &=\alpha \pi \frac{R^5}{5} \end{align}

- Divergence through a Prism

S1 5307S

Consider the vector field \(\vec F=(x+2)\hat{x} +(z+2)\hat{z}\).

-

Calculate the divergence of \(\vec F\).

\begin{align} \vec\nabla\cdot\vec F &= \frac{\partial}{\partial x} F_x + \frac{\partial}{\partial y} F_y + \frac{\partial}{\partial z} F_z\\ &= \frac{\partial}{\partial x} (x+2) + \frac{\partial}{\partial y} (0) + \frac{\partial}{\partial z} (z+2)\\ &= 2 \end{align}

Sense-making: The divergence is a scalar, so we got that much right. It is also a field, so in general it might depend on \(x\), \(y\), and \(z\). The fact that the divergence is uniform is arising from the linearity of the vector field's dependence on \(x\) and \(z\), and will make our job in the next questions easier!

-

In which direction does the vector field \(\vec F\) point on the plane

\(z=x\)? What is the value of \(\vec F\cdot \hat n\) on this plane

where \(\hat n\) is the unit normal to the plane?

On the plane \(z=x\), the \(x\) and \(z\) components of \(\vec F\) are equal, therefore \(\vec F\) points in the \(\hat\imath + \hat k\) direction, i.e. parallel to the plane. Therefore we see, without any further calculation, that \(\vec F \cdot \hat n\), the flux of \(\vec F\) through this plane is zero.

-

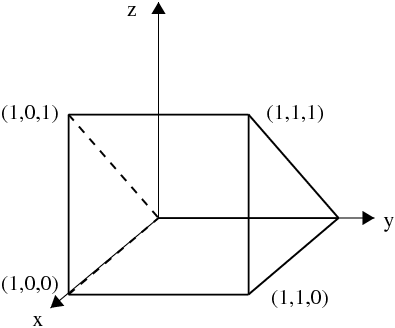

Verify the divergence theorem for this vector field where the volume

involved is drawn below. (“Verify” means calculate both sides of the divergence theorem, separately, for this example and show that they are the same.)

The divergence theorem states that the flux of any (sufficiently smooth) vector field through any closed surface is the same as the integral of the divergence of that vector field over the interior of the surface.

\begin{equation*} \oint \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA = \int \vec\nabla \cdot \vec F\, d\tau \end{equation*}

Calculating the left-hand side (the flux of the field through the surface of the prism): We showed in part (b) that there is no flux through the angled plane. There is also no flux through the triangular end pieces because \(\vec F\) has no \(\hat\jmath\) component (perpendicular to those planes).

The (outward) flux through the square bottom at the \(z=0\) plane is: \begin{align*} \int_{\text{bottom}} \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA &= \int_0^1\int_0^1 \left[(x+2)\hat x + (\cancelto{0}{z}+2)\hat z\right] \cdot (-\hat z)\, dx\, dy \\ &= \int_0^1\int_0^1 -2\, dx\, dy \\ &= -2 \end{align*}

Note that because I'm calculating the flux through surface of the prism in the \(z=0\) plane, I need to plug in \(z=0\)! The flux through the remaining vertical side is (at \(x=1\)):

\begin{align*} \int_{\text{side at }x=1} \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA &= \int_0^1\int_0^1 \left[3\hat x + (z+2)\hat z\right] \cdot (\hat x)\, dy\, dz \\ &=\int_0^1\int_0^1 3\, dy\, dz \\ &= 3 \end{align*}

Therefore, the left-hand side of the divergence theorem is:

\begin{align*} \oint \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA &= \int_{\text{bottom}} \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA + \cancelto{0}{\int_{\text{top}} \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA} + \cancelto{0}{\int_{\text{side at }y=0} \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA} + \cancelto{0}{\int_{\text{side at }y=1} \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA} + \int_{\text{side at }x=1} \vec F\cdot\hat n\, dA\\ &= -2+3\\ &=1 \end{align*}

Calculating the right-hand side, we have a constant divergence of 2, integrated over the prism shape which is half of the unit cube:

\begin{align*} \int \vec\nabla \cdot \vec F\, d\tau &= \int 2 d\tau \\ &= 2 \int_{\text{half a unit cube}} d\tau \\ &= (2) (\tfrac{1}{2}) \\ &= 1 \end{align*}

Therefore, we get just the divergence, 2, times the volume of the prism, 1/2. So the right-hand side of the divergence theorem also is 1, and we have verified the divergence theorem for this special case.

Sense-making: An interesting thing to note here is that since the divergence is uniform, choosing a bigger imaginary volume will always result in a larger net flux through that surface, no matter how large we choose the surface and no matter what shape and orientation we choose for the sides of that surface. You can also see that from the vector field, which keeps increasing in the \(x\)- and \(z\)-directions as \(x\) and \(z\) increase, respectively. Here it is the fact that the imaginary surface is closed that you want to pay attention to---you can easily pick one side of a closed surface to have zero flux, but when you close it the other sides will pick up what you tried to exclude.

-

Calculate the divergence of \(\vec F\).

- Electric Field and Charge

S1 5307S

Consider the electric field

\begin{equation}

\vec E(r,\theta,\phi) =

\begin{cases}

0&\textrm{for } r<a\\

\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \,\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\,

\left( r-\frac{a^3}{r^2}\right)\, \hat r & \textrm{for } a<r<b\\

0 & \textrm{for } r>b \\

\end{cases}

\end{equation}

- Use step and/or delta functions to write this electric field as a single

expression valid everywhere in space.

We need to turn the field on at \(r=a\) and off at \(r=b\), to do this we will use the combination of theta functions \(\Theta(r-a)-\Theta(r-b)\) and just multiply it by the given equation for \(a<r<b\) since it will be 0 for \(r<a\) and \(b<r\) and we have: \[ \vec{E}(r,\theta,\phi)=\frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \,\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\, \left( r-\frac{a^3}{r^2}\right)\left[\Theta(r-a)-\Theta(r-b)\right]\, \hat{r} \] The combination of \(\Theta\)'s: \(\Theta(r-a)\Theta(b-r)\), multiplied with the function in the same way is also a valid choice, as well as others!

- Find a formula for the charge density that creates this electric field.

We need to use Maxwell's equation for charge (i.e. the differential form of Gauss' Law) \[\vec\nabla \cdot \vec E=\frac{1}{\epsilon_0}\, \rho\] We will calculate the divergence in spherical coordinates. Don't forget to include the step functions and use the product rule! The divergence in spherical coordinates is: \begin{equation} \vec\nabla \cdot \vec E =\frac{1}{r^2}\frac{\partial}{\partial r}(r^2 E_r) +\frac{1}{r\sin\theta}\frac{\partial}{\partial\theta}(\sin\theta E_{\theta}) +\frac{1}{r\sin\theta}\frac{\partial}{\partial \phi}(E_{\phi}) \end{equation} Since our vector field is radial, (i.e. has only an \(\hat r\)-component), only the component \(E_r\) is nonzero, so only the first of these terms is relevant. Notice that you have to multiply the \(r\)-component of the vector field by \(r^2\) before differentiating. Therefore: \begin{align} \rho(r,\theta,\phi)&=\epsilon_0\vec\nabla\cdot\vec E\\ &=\epsilon_0\frac{1}{r^2}\frac{\partial}{\partial r} \left(r^2 \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \,\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\, \left( r-\frac{a^3}{r^2}\right)\left[\Theta(r-a)-\Theta(r-b)\right]\right)\\ &=\frac{1}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\,\frac{1}{r^2}\frac{\partial}{\partial r} \left(\left( r^3-a^3\right)\left[\Theta(r-a)-\Theta(r-b)\right]\right)\\ &=\frac{1}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\,\frac{1}{r^2} \left(\left( 3r^2\right)\left[\Theta(r-a)-\Theta(r-b)\right] +\left( r^3-a^3\right)\left[\delta(r-a)-\delta(r-b)\right] \right)\\ &=\frac{1}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3} \left(3\left[\Theta(r-a)-\Theta(r-b)\right] -\left( \frac{r^3-a^3}{r^2}\right)\delta(r-b) \right)\\ \end{align} The delta function at \(r=a\) does not contribute since the coefficient of that term is \(r^3-a^3\), which is zero at \(r=a\).

Sense-making: It is very important to note that you cannot simply assume the divergence is found by differentiating with respect to \(r\), i.e. \(\frac{\partial}{\partial r}\). The correct form of this term arises from the interpretation of the divergence as the flux per unit volume, and the fact that the flux through the inner and outer surfaces of a tiny spherical volume element (a pumpkin piece) will be through infinitesimal areas of different sizes!

- Interpret your formula for the charge density, i.e. explain briefly in words where the charge is.

There is a constant volume charge density with magnitude \(\frac{3}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\) inside a spherical shell for \(a<r<b\). The total charge due to this charge density can be found by integrating over the spherical shell: \begin{align} Q_{\text{total}}&=\frac{3}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3} \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{\pi}\int_a^b r^2\sin\theta\, dr\, d\theta\, d{\phi}\\ &=\frac{3}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\, 4\pi\int_a^b r^2\, dr\\ &=3\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}\left.\frac{r^3}{3}\right\vert_a^b\\ &=Q \end{align} (we see that the original constant \(Q\) is just the total charge on the spherical shell.)

There is also a surface charge density which is described as a volume charge density with a delta function at \(r=b\) with magnitude \(-\frac{1}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3} \frac{r^3-a^3}{r^2}\) on the surface of the sphere at \(r=b\). The total charge due to this surface charge density is found by integration: \begin{align} Q_{\text{total}}&=-\frac{1}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3} \int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{\pi}\int_a^b \left( \frac{r^3-a^3}{r^2}\right)\delta(r-b)\, r^2\sin\theta\, dr\, d\theta\, d{\phi}\\ &=-\frac{1}{4\pi}\frac{Q}{b^3-a^3}4\pi \int_a^b \left( r^3-a^3\right)\delta(r-b)\, dr\\ &=-Q \end{align} The two total charges are equal in magnitude and opposite in sign, so the total charge inside any sphere larger than the spherical shell is zero. Gauss's Law tells us that the electric field for \(r>b\) is zero, which we see in the original statement of the problem. If we had ommitted the step functions from the description of the electric field, we would not have had the delta function terms in the charge density, and we would not have seen how the electric field could be zero for \(r>b\).

Of course, all this could have been done with intuition and Gauss' Law, but the math checks out!

- Use step and/or delta functions to write this electric field as a single

expression valid everywhere in space.