Static Fields: Fall-2025

HW 07 (SOLUTION): Due W4 D3

- Flux Through a Cone

S1 5300S

Find the flux through a cone (with no cap!) of height \(H\) and radius \(R\) due to the vector field \(\vec{F} = C\,z\,\hat{z}\). The cone has its vertex at the origin, opens upward symmetrically around the z-axis. Orient your area elements so that upward pointing fields contribute positive flux.

This problem can be solved in either cylindrical and spherical coordinates.

Cylindrical Coordinates:

Chop the cone along slanted vertical lines \begin{align} \phi =\text{constant}&\Rightarrow d\phi=0\\ z=\frac{H}{R}\, s &\Rightarrow dz=\frac{H}{R}\, ds \end{align}

and horizontal circles \begin{align} s=\text{constant}&\Rightarrow ds=0\\ z=\text{constant}&\Rightarrow dz=0 \end{align}

Choose \(d\vec{r}_1\) and \(d\vec{r}_2\) so that the cross product gives an upward pointing vector. Find \(d\vec{A}=d\vec{r}_1\times d\vec{r}_2\). \begin{align} d\vec{r}_1 &= ds\, \hat{s}+\cancel{s\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}}+dz\, \hat{z}\\ &= ds\,\left(\hat{s}+\frac{H}{R}\, \hat{z}\right)\\ d\vec{r}_2&=\cancel{ds\, \hat{s}}+s\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}+\cancel{dz\, \hat{z}}\\ &= s\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}\\ d\vec{A}&=d\vec{r}_1\times d\vec{r}_2\\ &= ds\,\left(\hat{s}+\frac{H}{R}\, \hat{z}\right)\times s\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}\\ &= s\, ds\, d\phi\left(\hat{z}- \frac{H}{R}\, \hat{s} \right) \end{align} Putting all the pieces together, we have: \begin{align} \text{Flux}&=\int \vec{F}\cdot\vec{A}\\ &=\int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^R C\,z\,\hat{z}\cdot s\, ds\, d\phi\left(\hat{z}- \cancel{\frac{H}{R}\, \hat{s} }\right)\\ &=\int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^R C\,\frac{H}{R}\, s^2\, ds\, d\phi\\ &=2\pi C\,\frac{H}{R}\,\frac{1}{3} R^3\\ &=\frac{2\pi C}{3} HR^2 \end{align}

Spherical Coordinates:

Chop the cone along horizontal circles \begin{align} r=\text{constant}&\Rightarrow dr=0\\ \theta=\text{constant}&\Rightarrow d\theta=0 \end{align}

and along radial lines \begin{align} \phi=\text{constant}&\Rightarrow d\phi=0\\ \theta=\text{constant}&\Rightarrow d\theta=0 \end{align}

Choose \(d\vec{r}_1\) and \(d\vec{r}_2\) so that the cross product gives an upward pointing vector. Find \(d\vec{A}=d\vec{r}_1\times d\vec{r}_2\). \begin{align} d\vec{r}_1&=dr\, \hat{r}+\cancel{r\, d\theta\, \hat{\theta}} +\cancel{r\sin\theta\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}}\\ &=dr\, \hat{r}\\ d\vec{r}_2&=\cancel{dr\, \hat{r}}+\cancel{r\, d\theta\, \hat{\theta}} +r\sin\theta\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}\\ &=r\sin\theta\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}\\ d\vec{A}&=d\vec{r}_1\times d\vec{r}_2\\ &=dr\, \hat{r}\times r\sin\theta\, d\phi\, \hat{\phi}\\ &=-r\sin\theta\, dr\, d\phi\, \hat{\theta} \end{align}

When we take the dot product of the vector field with the unit normal to the cone, we will have to evaluate \(-\hat{z}\cdot\hat{\theta}=\sin{\theta}\) which you can see most easily by drawing a picture. Also recall that \(z=r\cos\theta\). Putting all the pieces together, we have: \begin{align} \text{Flux}&=\int \vec{F}\cdot\vec{A}\\ &= -\int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}} C\,z\,\hat{z}\cdot r\sin\theta\, dr\, d\phi\, \hat{\theta}\\ &= \int_0^{2\pi} \int_0^{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}} C\,r^2\cos\theta\, \sin^2\theta\, dr\, d\phi\\ &= 2\pi C\,\left.\frac{r^3}{3}\right\vert_0^{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}} \frac{H}{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}}\left(\frac{R}{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}}\right)^2\\ &= \frac{2\pi C}{3} HR^2 \end{align}

- Gauss's Law on a Cylindrical Shell

S1 5300S

Consider an infinite positively charged (dielectric) cylindrical shell of inner radius \(a\) and outer radius \(b\) with a cylindrically symmetric internal charge density \(\rho(\vec r)=\alpha\, e^{(ks)^2}\).

Answer each of the following questions:

- Use Gauss's Law and symmetry arguments to find the electric field at

each of the three radii below:

- \(s>b\)

- \(a<s<b\)

- \(s<a\)

- What dimensions do \(\alpha\) and \(k\) have?

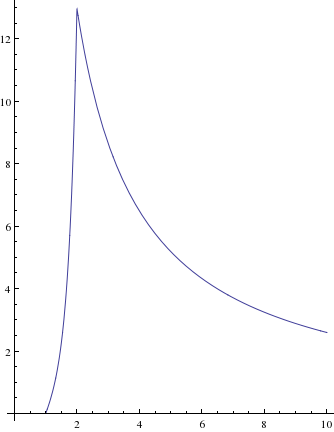

- For \(\alpha=1\), \(k=1\), sketch the magnitude of the electric field as a function of \(s\).

-

By symmetry, the electric field only has a (cylindrical) radial component, and can only depend on the cylindrical radial coordinate \(s\), so \(\boldsymbol{\vec{E}}=E_s(s)\,\boldsymbol{\hat{s}}\).

Choose the Gaussian surface to be a finite cylinder of height \(L\)

and radius \(s\). Then the flux of \(\boldsymbol{\vec{E}}\) out of the cylinder is

\[\int_C\boldsymbol{\vec{E}}\cdot d\boldsymbol{\vec{A}}

= \int_C E_s(s)\,dA = 2\pi sLE_s\]

The charge \(Q_{enc}\) in the region \(R\) inside the cylinder \(C\) is

\[Q_{enc}=\int_R \rho\,d\tau\]

so Gauss's Law tells us that

\[E_s = \frac{Q_{enc}}{2\pi sL\epsilon_0}\]

- For \(s>b\), the enclosed charge is \[Q_{enc}=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^L\int_a^b \rho s\,ds\,dz\,d\phi = 2\pi L \int_a^b \alpha\,e^{(ks)^2}\,s\,ds = \frac{\pi L\alpha}{k^2} e^{(ks)^2}\bigg|_a^b\] so that \[E_s = \frac{\alpha}{2sk^2\epsilon_0}\left(e^{(kb)^2}-e^{(ka)^2}\right)\]

- For \(a<s<b\), the only thing that changes is the limits, and the enclosed charge is \[Q_{enc} = \frac{\pi L\alpha}{k^2} e^{(ks)^2}\bigg|_a^s\] so that \[E_s = \frac{\alpha}{2sk^2\epsilon_0}\left(e^{(ks)^2}-e^{(ka)^2}\right)\]

- For \(s<a\), \(Q_{enc}=0\), so \(E_s=0\).

- The quantity \(ks\) is dimensionless, and \(s\) has the dimensions of length, so \(k\) must have the dimensions of inverse length. Similarly, since \(\rho\) is a (volume) charge density, it has dimensions of \(\frac{\mathrm{charge}}{\mathrm{length}^3}\). Since the exponential factor must be dimensionless, these are also the dimensions of \(\alpha\).

Also setting \(a=1\), \(b=2\), and \(\epsilon_0=1\) yields a graph of the form below.

- Use Gauss's Law and symmetry arguments to find the electric field at

each of the three radii below:

- Spherical Shell Step Functions

S1 5300S

One way to write volume charge densities without using piecewise functions is to use step \((\Theta)\) or delta (\(\delta\)) functions. Consider a spherical shell with charge density \[\rho (\vec{r})=\alpha3e^{(k r)^3} \]

between the inner radius \(a\) and the outer radius \(b\). The charge density is zero everywhere else.

- What are the dimensions of the constants \(\alpha\) and \(k\)?

\(\alpha\) is the only dimensionful thing outside the exponential, so it needs to have the same dimensions as \(\rho\) which is \(\frac{[charge]}{[volume]}\) or \(\frac{[Q]}{[L^3]}\). The exponential itself needs to have no dimensions in the exponents, so \(k\) needs to have dimensions of \(\frac{1}{[L]}\) to cancel the length dimensions in \(r\).

- By hand, sketch a graph the charge density as a function of \(r\) for \(\alpha > 0\) and \(k>0\) .

- Use step functions to write this charge density as a single function valid everywhere in space.

\[\rho (\vec{r})=\alpha3e^{(k r)^3}\left[\Theta(r-a)-\Theta(r-b)\right]\]

- What are the dimensions of the constants \(\alpha\) and \(k\)?

- Mass of a Slab

S1 5300S

Determine the total mass of each of the slabs below.

-

A square slab of side length \(L\) with thickness \(h\), resting on a

table top at \(z=0\), whose mass density is given by

\begin{equation*}

\rho=A\pi\sin\left[\tfrac{\pi z}h\right].

\end{equation*}

\begin{align*} M &= \int\limits_{\hbox{slab}} \rho \,dV\\ &= \int\limits_{0}^L\int\limits_{0}^L\int\limits_0^h A\pi\sin\left[\tfrac{\pi z}h\right] \,dz\, dx\, dy\\ &= L^2 \int\limits_0^h A\pi\sin\left[\tfrac{\pi z}h\right] \,dz\\ &= 2 A h L^2 \end{align*}

-

A square slab of side length \(L\) with thickness \(h\), resting on a

table top at \(z=0\), whose mass density is given by

\begin{equation*}

\rho = 2A \Big[\Theta(z)-\Theta(z-h) \Big]

\end{equation*}

\begin{align*} M &= \int\limits_{\hbox{slab}} \rho \,dV\\ &= \int\limits_{0}^L\int\limits_{0}^L\int\limits_{-\infty}^\infty 2A\Big[\Theta(z)-\Theta(z-h) \Big] \,dz\, dx\, dy\\ &= L^2 \int\limits_{-\infty}^\infty 2A \Big[\Theta(z)-\Theta(z-h) \Big] \,dz\\ &= L^2 \int\limits_0^h 2A \,dz\\ &= 2 A h L^2 \end{align*}

-

An infinitesimally thin square sheet of side length \(L\), resting on

a table top at \(z=0\), whose surface density is given by

\(\sigma=2Ah\).

Since the surface density is constant, we simply multiply the mass density by the area of the slab, obtaining \begin{equation*} m = \sigma L^2 = 2 A h L^2 \end{equation*}

-

An infinitesimally thin square sheet of side length \(L\), resting on

a table top at \(z=0\), whose mass density is given by

\(\rho=2Ah\,\delta(z)\).

\begin{align*} M &= \int\limits_{\hbox{slab}} \rho \,dV\\ &= L^2 \int\limits_{-\infty}^\infty 2Ah\,\delta(z) \,dz\\ &= 2 A h L^2 \end{align*}

-

What are the dimensions of \(A\)?

\(A\) is a mass density with dimensions: \(\left[A\right]=\frac{M}{L^3}\) so that when we multiply it by the volume \(\left[L^2 h\right]\) we get a total mass.

-

Write several sentences comparing your answers to the different cases above.

All of these slabs could represent the same physical system and have the same mass, but measured with different amounts of precision. The second can be viewed as an idealization of the first, in which the internal structure of the slab doesn't matter. The last two are further idealizations of the second in which the thickness of the slab is imagined to be infinitely thin. One accomplishes this by describing the density as a surface density \(\sigma\), the other accomplishes this by recognizing that all densitites are volume densities, but describes the functional dependence in the third dimension as a delta function \(\delta(z)\).

-

A square slab of side length \(L\) with thickness \(h\), resting on a

table top at \(z=0\), whose mass density is given by

\begin{equation*}

\rho=A\pi\sin\left[\tfrac{\pi z}h\right].

\end{equation*}