Static Fields: Fall-2025

HW 07 Practice (SOLUTION): Due W4 D3

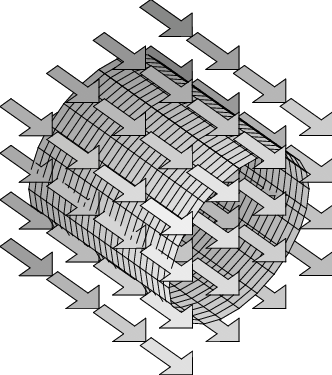

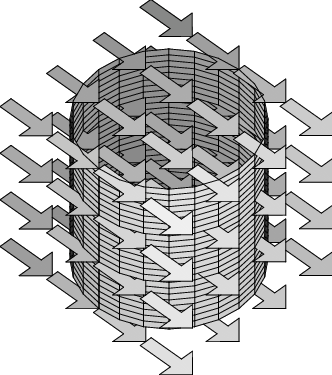

- Flux through a Cylinder

S1 5299S

- What do you think will be the flux through the cylindrical surface that is placed as shown in the constant vector field in the first figure?

- What if the cylinder is placed upright, as shown in the second figure? Explain.

In the first figure, the vector field is everywhere parallel to the cylinder, so the flux must be zero. In the second figure, although there is nonzero flux locally, the symmetry of the cylinder (and the constancy of the vector field) ensures that the flux in on the left is the same as the flux out on the right, so that the total flux is again zero.

- Flux I

S1 5299S

Find the flux of

\(\boldsymbol{\vec F}

=x\,\boldsymbol{\hat x}+y\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}

+z\,\boldsymbol{\hat z}\)

out of a closed cylinder of radius 2 centered on the \(z\)-axis, with \(-3\le z\le3\).

Look before you leap!

Flux is given by \(\displaystyle\int\boldsymbol{\vec F}\cdot d\boldsymbol{\vec A}\), where \(\boldsymbol{\vec A}=\boldsymbol{\hat n}\,dA\). For the sides of the cylinder, \(\boldsymbol{\hat n}=\boldsymbol{\hat r} =\frac1r(x\,\boldsymbol{\hat x}+y\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}\)), so \(\boldsymbol{\vec F}\cdot\boldsymbol{\hat n} =\frac{x^2+y^2}{r}=r=2\), so the flux through the sides is just twice the area, namely \(2\pi rh=2\pi(2)(6)=24\pi\).

For the two caps, \(\boldsymbol{\hat n}=\pm\boldsymbol{\hat z}\), so \(\boldsymbol{\vec F}\cdot\boldsymbol{\hat n}=\pm z=+3\) in both cases, so the flux through the caps is \(3+3\) times the area, namely \(6\pi r^2=24\pi\).

Adding up the pieces, the total flux out of the cylinder is \(48\pi\).

- Flux II

S1 5299S

Find the flux of \(\boldsymbol{\vec F}=z^2\,\boldsymbol{\hat z}\) through the upper hemisphere of the sphere \(x^2+y^2+z^2=25\), oriented away from the origin.

Working in spherical coordinates, the angle between \(\boldsymbol{\hat z}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\hat n}=\boldsymbol{\hat r}\) is clearly the spherical angle \(\theta\) (colatitude). Furthermore, since the vertical projection of \(r\,\boldsymbol{\hat r}\) is \(z\,\boldsymbol{\hat z}\), we also have \(z=r\,\cos\theta\). Thus, \(\boldsymbol{\vec F}\cdot\boldsymbol{\hat n} = z^2\cos\theta = r^2\cos^3\theta\). So \begin{align*} \int\boldsymbol{\vec F}\cdot d\boldsymbol{\vec A} &= \int r^2\cos^3\theta\,dA \\ &= \int r^2\cos^3\theta (r^2\sin\theta\,d\theta\,d\phi) \\ &= 2\pi r^4 \int \cos^3\theta\sin\theta\,d\theta \\ &= -2\pi r^4 \frac{\cos^4\theta}{4} \bigg|_0^{\pi/2} = \frac{625\pi}{2} \end{align*}

- Flux III

S1 5299S

Let

\(\boldsymbol{\vec H}

= (e^{xy}+3z+5)\,\boldsymbol{\hat x}

+ (e^{xy}+5z+3)\,\boldsymbol{\hat y} + (3z+e^{xy})\,\boldsymbol{\hat z}\).

Calculate the flux of \(\boldsymbol{\vec H}\) through the square of side \(2\) with one vertex at the origin, one edge along the positive \(y\)-axis, one edge in the \(xz\)-plane with \(x>0\), \(z>0\), and with normal

\(\boldsymbol{\hat n}=\boldsymbol{\hat x}-\boldsymbol{\hat z}\).

Flux is given by \(\displaystyle\int\boldsymbol{\vec F}\cdot d\boldsymbol{\vec A}\), where \(\boldsymbol{\vec A}=\boldsymbol{\hat n}\,dA\). Since \(\boldsymbol{\hat n}\) is given, compute the dot product: \(\boldsymbol{\vec F}\cdot\boldsymbol{\hat n}=5\). Thus, the flux through the square is 5 times the area, namely \(5(2^2)=20\).

- Flux through a Plane

S1 5299S

Find the upward pointing flux of the vector field \(\boldsymbol{\vec{H}}=2z\,\boldsymbol{\hat{x}}

+\frac{1}{x^2+1}\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}+(3+2z)\boldsymbol{\hat{z}}\) through the rectangle \(R\) with one edge along the \(y\) axis and the other in the \(xz\)-plane along the line \(z=x\), with \(0\le y\le2\) and \(0\le x\le3\).

The plane lies at a 45-degree angle in the \(xz\)-plane, so along lines with \(y=\hbox{const}\), we have \(dy=0\) and \(dz=dx\), so \(d\boldsymbol{\vec{r}}_1 =dx\,\boldsymbol{\hat{x}}+dx\,\boldsymbol{\hat{z}}\). Along lines in the \(y\) direction, \(x\) and \(z\) are constant, so \(d\boldsymbol{\vec{r}}_2=dy\,\boldsymbol{\hat{y}}\). Therefore, \[d\boldsymbol{\vec{A}} =d\boldsymbol{\vec{r}}_1\times d\boldsymbol{\vec{r}}_2 =dx\,dy\,(\boldsymbol{\hat{x}}+\boldsymbol{\hat{z}})\times \boldsymbol{\hat{y}} =dx\,dy\,(\boldsymbol{\hat{z}}-\boldsymbol{\hat{x}}).\] Since the coefficient of \(\boldsymbol{\hat{z}}\) is positive, we have indeed chosen the correct orientation.

The flux integral now becomes \[\int_R \boldsymbol{\vec{H}}\cdot d\boldsymbol{\vec{A}} = \int_R \bigl((3+2z)-2z\bigr)\,dx\,dy = \int_0^2 \int_0^3 3\,dx\,dy = 18 . \]

- Gauss's Law for a Rod inside a Cube

S1 5299S

Consider a thin charged rod of length \(L\) standing along the \(z\)-axis

with the bottom end on the \(x,y\)-plane.

The charge density \(\lambda_0\) is constant.

Find the total flux of the electric field through a closed cubical

surface with sides of length \(3L\) centered at the origin.

This is a straightforward Gauss's Law problem: \begin{align} \oint \vec{E}\cdot \hat{n}\, dA &=\frac{1}{\epsilon_0} Q_{\text{enclosed}}\\ &=\frac{1}{\epsilon_0}\int_0^L \lambda_0 dz\\ &=\frac{1}{\epsilon_0}\lambda_0 L \end{align}

- Volume Charge Density

S1 5299S

Consider the volume charge density: \begin{equation*} \rho (x,y,z)=c\,\delta (x-3) \end{equation*}

- Describe in words how this charge is distributed in space.

This equation represents a charged plane oriented parallel to the \(y,z\)-plane and located at \(x=3\).

- What are the dimensions of the constant \(c\)?

The delta function has dimensions of inverse length, and the volume charge density has dimensions of charge per length cubed, so \(c\) has dimensions of charge per length squared.

- Describe in words how this charge is distributed in space.