Static Fields: Fall-2025

HW 06 Practice (SOLUTION): Due W3 D5

- Electric Field from a Rod

S1 5293S

Consider a thin charged rod of length \(L\) standing along the \(z\)-axis

with the bottom end on the \(xy\)-plane.

The charge density \(\lambda\) is constant.

Find the electric field at the point \((0,0,2L)\).

The rod lies along the \(z\)-axis, and I'm finding the electric field at a distance \(L\) above the top of the rod. I'll use cylindrical coordinates to compute the electric field.

The vector pointing toward the point where the potential is evaluated is: \begin{equation} \vec{r} = 2L\hat{z} \end{equation} The vector pointing toward an infinitesimal piece of charge is: \begin{equation} \vec{r}\,' = z'\hat{z} \end{equation} The electric field is: \begin{align} \vec{E}(0,0,2L) &= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \int_{0}^{L} \frac{\lambda\, (\vec{r}-\vec{r}\,')\,d\ell'}{|\vec{r}-\vec{r}\,'|^3}\\ &= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0}\int_{0}^{L} \frac{\lambda\, (2L -z')\hat{z}\, dz'}{\vert 2L -z'\vert^{3}}\\ &= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \lambda \,\hat{z}\int_{0}^{L} (2L-z')^{-2}\, dz'\\ &= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \lambda \,\hat{z}\, (2L-z')^{-1}\Big|_0^L\\ &= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \lambda \left(\frac{1}{L}-\frac{1}{2L}\right)\,\hat{z}\\ &= \frac{1}{4\pi\epsilon_0} \frac{\lambda}{2L}\,\hat{z} \end{align}

- Electric Field Due to a Ring - Limiting Cases

S1 5293S

In class, we considered the electric field due to a charged ring with total charge \(Q\) and radius \(R\).

Find the first two non-zero terms of a series expansion for the electric field at each of these special locations:

\begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})=\frac{kQ}{2\pi} \int \frac{\left(\left(s \cos\phi -R \cos\phi'\right) \hat x + \left(s \sin\phi -R \sin\phi'\right)\hat y + z \hat z\right)}{\left(s^2+R^2-2sR\cos(\phi-\phi')+z^2\right)^\frac{3}{2}}d\phi' \end{align}

Near the center of the ring, on the axis perpendicular to the plane of the ring;

Looking at the region where \(R\ll z\), on the axis of symmetry, we immediately set \(s=0\) and we have: \begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})=-\frac{kQR}{2\pi} \int \frac{\cos(\phi') \hat x }{\left(R^2+z^2\right)^\frac{3}{2}}d\phi'\\ -\frac{kQR}{2\pi} \int \frac{\sin(\phi')\hat y} {\left(R^2+z^2\right)^\frac{3}{2}}d\phi'\\ +\frac{kQ}{2\pi} \int \frac{z \hat z}{\left(R^2+z^2\right)^\frac{3}{2}}d\phi' \end{align} The x and y components integrate to 0 since sine and cosine give 0 over the range of 0 to \(2\pi\), and the z component doesn't depend on \(\phi'\), so we just get \(2\pi\) out of that integral and have: \begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})= kQ \frac{z \hat z}{\left(R^2+z^2\right)^\frac{3}{2}} \end{align} If we expand under big R, we have: \begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})= kQ \left(\frac{z}{R^3}-\frac{3z^3}{2R^5}\right)\hat z \end{align}

Far from the ring, in the plane of the ring;

\begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})=\frac{kQ}{2\pi} \int \frac{\left(\left(s \cos\phi -R \cos\phi'\right) \hat x + \left(s \sin\phi -R \sin\phi'\right)\hat y + z \hat z\right)}{\left(s^2+R^2-2sR\cos(\phi-\phi')+z^2\right)^\frac{3}{2}}d\phi' \end{align}

I can begin investigating the region where \(R \ll s\), in the plane where \(z=0\), so my approximation for the denominator in all 3 terms becomes: \begin{align} \frac{1}{|\vec{r}-\vec{r}'|^3}=\left(s^2+R^2-2sR\cos(\phi-\phi')\right)^{-\frac{3}{2}} \end{align} We approximate this with the power series \((1+z)^p\approx 1+pz+\frac{p(p-1)}{2!}z^2+...\), where we pull out s since it is large in the region we are looking at: \begin{align} \frac{1}{s^3}\left(1+\frac{R^2}{s^2}-2\frac{R}{s}\cos(\phi-\phi')\right)^{-\frac{3}{2}} &\approx \frac{1}{s^3}\left(1+\left(-\frac{3}{2}\right)\left(\frac{R^2}{s^2}-2\frac{R}{s}\cos(\phi-\phi')\right) \right) \\ &= \frac{1}{s^3}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^5}+3\frac{R}{s^4}\cos(\phi-\phi') \end{align} Now we put this back into our integral equations: \begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})=\frac{kQ}{2\pi} \int \left(s \cos(\phi) -R \cos(\phi')\right) \hat x \left( \frac{1}{s^3}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^5}+3\frac{R}{s^4}\cos(\phi-\phi')\right) d\phi'\\ +\frac{kQ}{2\pi} \int \left(s \sin(\phi) -R \sin(\phi')\right)\hat y \left( \frac{1}{s^3}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^5}+3\frac{R}{s^4}\cos(\phi-\phi')\right)d\phi'\\ +\frac{kQ}{2\pi} \int z \hat z\left( \frac{1}{s^3}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^5}+3\frac{R}{s^4}\cos(\phi-\phi')\right) d\phi' \end{align}

Any term with a single trig function of \(\phi'\) drops out, and we impose \(z=0\) to kill off the \(\hat z\) component entirely: \begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})=\frac{kQ}{2\pi} \int \left(s \cos(\phi)\left( \frac{1}{s^3}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^5}\right) -R \cos(\phi')\left( 3\frac{R}{s^4}\cos(\phi-\phi')\right)\right) \hat x d\phi'\\ +\frac{Q}{8\pi^2 \epsilon_0} \int \left(s \sin(\phi)\left( \frac{1}{s^3}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^5}\right) -R \sin(\phi')\left( 3\frac{R}{s^4}\cos(\phi-\phi')\right)\right)\hat y d\phi' \end{align} The first two terms in each component do not depend on \(\phi'\), so they simply integrate to \(2\pi\), the terms with 2 trig functions will integrate to \(\pi\) times \(sin(\phi)\) or \(cos(\phi)\) just like they did before, so we have: \begin{align} \vec{E}(\vec{r})=kQ \left( \cos(\phi)\left( \frac{1}{s^2}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^4}\right) - \frac{3R^2}{2s^4}\cos(\phi)\right) \hat x\\ + kQ \left( \sin(\phi)\left( \frac{1}{s^2}-\frac{3R^2}{2s^4}\right) - \frac{3R^2}{2s^4}\sin(\phi)\right) \hat y\\ =kQ \left( \frac{1}{s^2}-\frac{3R^2}{s^4}\right)\left( \cos(\phi) \hat x+\sin(\phi) \hat y\right)\\ =kQ \left( \frac{1}{s^2}-\frac{3R^2}{s^4}\right)\hat s \end{align} Where we used the identity for \(\hat s= \cos(\phi) \hat x+\sin(\phi) \hat y\) that we saw before.

- Cross Triangle

S1 5293S

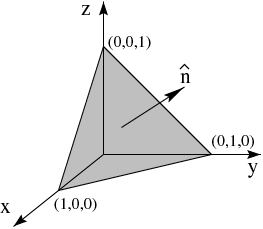

Use the cross product to find the components of the unit vector \(\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat n}}\) perpendicular to the plane shown in the figure below, i.e. the plane joining the points \(\{(1,0,0),(0,1,0),(0,0,1)\}\).

Take the cross product of any two vectors in the plane. For example, the vector \(-\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat x}}+\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat y}}\) that points from \((1,0,0)\) to \((0,1,0)\) and the vector \(-\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat x}}+\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat{z}}}\) that points from \((1,0,0)\) to \((0,0,1)\). The result is perpendicular to the plane. Make sure that the right hand rule gives the vector out of the plane in the direction that you want. Normalize the resulting vector to obtain: \[\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat n}} = \frac{1}{\sqrt{3}}\left(\mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat x}} + \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat y}} + \mathbf{\boldsymbol{\hat{z}}}\right)\]

This answer makes sense because the surface we are finding is one of the faces of a tetrahedron bounded by a cube, and the normal vector should point equally in the three directions because it must point toward one of the opposite corners of the cube!

- Directional Derivative

S1 5293S

You are on a hike. The altitude nearby is described by the function \(f(x, y)= k x^{2}y\), where \(k=20 \mathrm{\frac{m}{km^3}}\) is a constant, \(x\) and \(y\) are east and north coordinates, respectively, with units of kilometers. You're standing at the spot \((3~\mathrm{km},2~\mathrm{km})\) and there is a cottage located at \((1~\mathrm{km}, 2~\mathrm{km})\). You drop your water bottle and the water spills out.

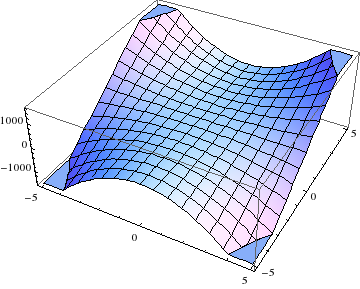

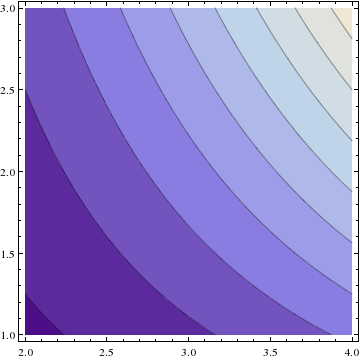

- Plot the function \(f(x, y)\) and also its level curves in your favorite plotting software. Include images of these graphs. Special note: If you use a computer program written by someone else, you must reference that appropriately.

- In which direction in space does the water flow?

- At the spot you're standing, what is the slope of the ground in the direction of the cottage?

- Does your result to part (c) make sense from the graph?

-

A plot of the function \(20x^2y\) as well as a contour diagram near the point \((3,2)\) appear below.

- First find the gradient of the function \(f\) at your location: \begin{align} \vec\nabla f &= (\hat{x}\, \frac{\partial}{\partial x} + \hat{y}\, \frac{\partial}{\partial y})\, f \nonumber\\ &= (2kxy\,\hat{x} + kx^2\, \hat{y}) \nonumber\\ &= (240\, \hat{x} +180\,\hat{y}) \mathrm{\frac{m}{km}} \nonumber\\ &= \frac{3}{10} \left(\frac45\,\hat{x}+\frac35\,\hat{y}\right) \end{align} since \(1\,\mathrm{km}=1000\,\mathrm{m}\). Notice that, since \(f\) is a function of only two variables, the gradient is a two-dimensional vector, i.e. it lives on the topo map, not in three-dimensional space. So \(\vec\nabla f\) gives the compass direction which points most steeply uphill. How steep is the hill in that direction? The maximum slope is given by \(|\vec\nabla f|\). So the ratio of vertical distance traveled (the rise) to horizontal distance traveled (the run) is \(|\vec\nabla f|\). A vector pointing uphill is therefore \(\vec{v}=\vec\nabla f + |\vec\nabla f|^2\,\hat{z}\). (Do you see why the magnitude is squared in the last term?) However, water flows downhill, so the water flows along \(-\vec{v}\). Putting this all together, the water flows in space in the direction given by \begin{equation} -\vec{v} =-\frac{3}{10} \left(\frac45\vec{x}+\frac35\hat{y}+\frac{3}{10}\hat{z}\right) \end{equation} which can be normalized if desired to give a pure direction.

- The gradient contains all of the information needed to find the slope in any direction. The two-dimensional unit vector \(\hat{u}\) that points in the direction pointing from your current position to the cottage is obtained by subtracting the corresponding position vectors, that is: \begin{align} \vec r_{\textrm{you}}&=3 \hat{x} + 2 \hat{y}\\ \vec r_{\textrm{cottage}}&=1 \hat{x} + 2 \hat{y}\\ \vec u &=\vec r_{\textrm{cottage}}-\vec r_{\textrm{you}}=-2\hat{x}\\ \hat u &=\frac{\vec u}{|\vec u|}=-\hat{x} \end{align} The directional derivative that you want is the dot product of the gradient with the appropriate unit vector: \begin{align} \vec\nabla f \cdot \hat u &= (240\, \hat{x} +180\, \hat{y}) \mathrm{\frac{m}{km}}\cdot (-\hat{x}) \nonumber\\ &= -240 \mathrm{\frac{m}{km}} \end{align}

- Zooming in on the graph confirms that the slope in this direction should indeed be negative.