Static Fields: Fall-2025

HW 03 Practice (SOLUTION): Due W2 D3

- Vector Sketch (Rectangular Coordinates)

S1 5284S

Sketch each of the vector fields below.

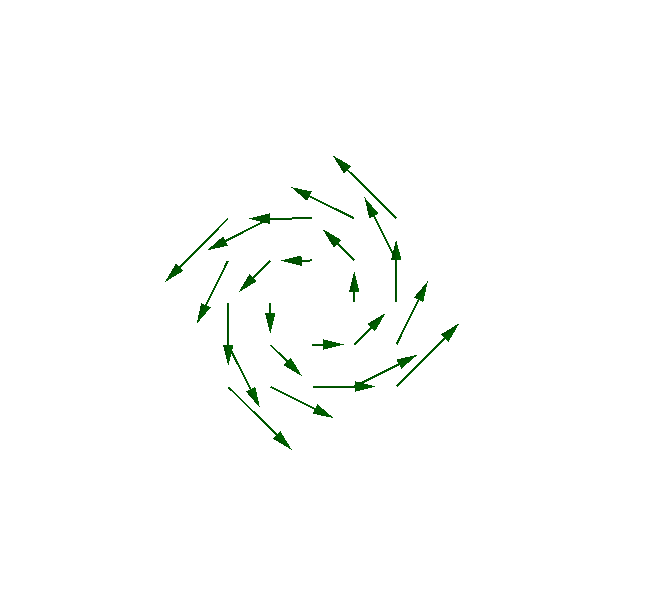

- \(\boldsymbol{\vec F} =-y\,\boldsymbol{\hat x} + x\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}\)

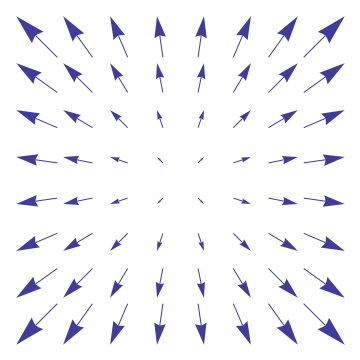

- \(\boldsymbol{\vec G} = x\,\boldsymbol{\hat x} + y\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}\)

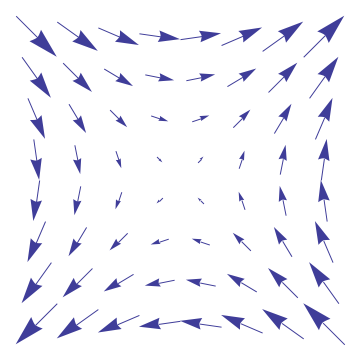

- \(\boldsymbol{\vec H} = y\,\boldsymbol{\hat x} + x\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}\)

-

\(\boldsymbol{\vec F}=-y\,\boldsymbol{\hat x} + x\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}=s\,\boldsymbol{\hat\phi}\)

-

\(\boldsymbol{\vec G}= x\,\boldsymbol{\hat x} + y\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}=s\,\boldsymbol{\hat s}\)

-

\(\boldsymbol{\vec H} = y\,\boldsymbol{\hat x} + x\,\boldsymbol{\hat y}\)

- Distance Formula in Curvilinear Coordinates

S1 5284S

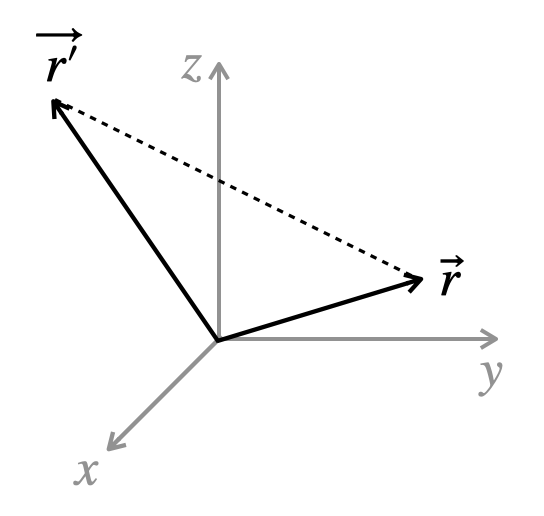

The distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\) and the point \(\vec r'\) is a coordinate-independent, physical and geometric quantity. But, in practice, you will need to know how to express this quantity in different coordinate systems.

Find the distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\) and the point \(\vec r'\) in rectangular coordinates.

In rectangular coordinates: \begin{align} \left| \vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \left|(x\hat{x}+y\hat{y}+z\hat{z}) -(x\,{}'\hat{x}+y\,{}'\hat{y}+z\,{}'\hat{z})\right|\\ &= \left|((x-x')\hat{x}+(y-y')\hat{y}+(z-z')\hat{z}) \right|\\ &= \sqrt{((x-x')\hat{x}+(y-y')\hat{y}+(z-z')\hat{z}) \cdot ((x-x')\hat{x}+(y-y')\hat{y}+(z-z')\hat{z})}\\ &= \sqrt{(x-x\,{}')^2+(y-y\,{}')^2+(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{align}

Sense-making: This is the Pythagorean Theorem!

Show that this same distance written in cylindrical coordinates is: \begin{equation*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| =\sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{equation*}

Hint: You may want to use the textbook: GMM: Change of Coordinates

In cylindrical coordinates: \begin{align*} x &= s\cos\phi\\ y &= s\sin\phi\\ z &= z \end{align*} Plug these coordinates into the ANSWER to the first part, above. Then simplify using appropriate trig identities including an addition formula. Now would be a good time to learn how to find the trig identities quickly online or in a reference book.

(Note: You might be tempted to do this calculation by starting with an expression for the position vector using both cylindrical coordinates and cylindrical basis vectors. This strategy is impossible because the cylindrical basis vectors at \(\vec r\) and \(\vec r'\) are different from each other, so you cannot subtract these vectors without resorting to fancy differential geometry/general relativity! If you don't yet know about cylindrical basis vectors, ignore this comment for now.)

\begin{align*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \sqrt{(s\cos\phi-s\,{}'\cos\phi\,{}')^2 +(s\sin\phi-s\,{}'\sin\phi\,{}')^2 + (z-z\,{}')^2}\\ &= \left[s^2(\cos^2\phi+\sin^2\phi) +s\,{}'^2(\cos^2\phi\,{}'+\sin^2\phi\,{}')\right.\\ &~~~\left. -2s\,{}' s(\cos\phi\cos\phi\,{}'+\sin\phi\sin\phi\,{}') +(z-z\,{}')^2\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}\\ &= \sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')+(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{align*}

Show that this same distance written in spherical coordinates is: \begin{equation*} \left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert =\sqrt{r'^2+r\,{}^2-2rr\,{}' \left[\sin\theta\sin\theta\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}'\right]} \end{equation*}

Hint: You may want to use the textbook: GMM: Change of Coordinates

In spherical coordinates: \begin{align*} x &= r\sin\theta \cos\phi\\ y &= r\sin\theta \sin\phi\\ z &= r\cos\theta \end{align*} Plug these coordinates into the ANSWER to the first part, above. Also, see the notes in the solution to the cylindrical case. \begin{align*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \left[(r\sin\theta \cos\phi-r\,{}'\sin\theta\,{}'\cos\phi\,{}')^2\right.\\ &~~\left. +(r\sin\theta\sin\phi -r\,{}'\sin\theta\,{}' \sin\phi\,{}')^2\right.\\ &~~\left. +(r\cos\theta -r\,{}'\cos\theta\,{}')^2\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}\\ &= \left\{ r^2 [\sin^2\theta(\cos^2\phi +\sin^2\phi)+\cos^2\theta]\right.\\ &~~\left. +r\,{}'^2 [\sin^2\theta\,{}'(\cos^2\phi\,{}'+\sin^2\phi\,{}') +\cos^2\theta\,{}' ]\right.\\ &~~\left. -2rr\,{}'[\sin\theta \sin\theta\,{}'(\cos\phi\cos\phi\,{}' +\sin\phi\sin\phi\,{}')+\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}']\right\} ^{\frac{1}{ 2}}\\ &=\sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}'[\sin\theta \sin\theta\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}']} \end{align*}

Sense-making: Wow, that is an ugly expression (don't memorize this one, by the way). Let's try some special cases. If \(\phi = \phi\,{}'\), we can use a trig identity to reduce the distance formula to \begin{equation*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| = \sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}' \cos\left(\theta - \theta\,{}'\right)} \end{equation*}

This is the law of cosines, which makes sense because you can easily write the angle between the two vectors in terms of the difference in the polar angles \(\theta\). The same trick doesn't work the same way for \(\theta = \theta\,{}'\), since the difference in \(\phi\) is not the difference in angles---unless \(\theta = \theta\,{}' = \pi/2\), which is on the equator (see next part).

-

Now assume that \(\vec r\,{}'\) and \(\vec r\) are in the \(x\)-\(y\) plane. Simplify

the previous two formulas.

Cylindrical Coordinates at \(z=0\) and \(z\,{}'=0\) \begin{equation*} \sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')} \end{equation*}

Spherical Coordinates at \(\theta\,{}'=\frac{\pi}{2}\Rightarrow \cos\theta\,{}'=0\) and \(\sin\theta\,{}'=1\). (Also true for \(\theta\).) \begin{equation*} \sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')} \end{equation*}

Behold the Law of Cosines once again!

- Power Series Practice

S1 5284S

- Calculate the \(n=0, 1, 2, 3, 4\) coefficients of the power series for \(\cos{z}\) expanded around \(z=\pi\). Using these coefficients, find a power series approximation for this function.

First, the form of the answer will be: \[ \cos z \approx c_0 + c_1 (z-\pi) + c_2 (z-\pi)^2 + c_3(z-\pi)^3 + c_4(z-\pi)^4\] or \[ \cos z = c_0 + c_1 (z-\pi) + c_2 (z-\pi)^2 + c_3(z-\pi)^3 + c_4(z-\pi)^4+\dots\]

Because I'm asked for the fourth order expansion, I'll keep only terms up to the fourth power. I use the first form (with the \(\approx\) approximation sign and stopping at the fourth order term) when I want to emphasize that I have done an approximation. Ise the second form (with an \(=\) sign and \(\dots\) at the end) when I want to indicate that there are more terms that I am not writing in the exact power series.

Now, to calculate the coefficients: \begin{eqnarray*} c_0 &=& \frac{1}{0!}f(z=z_0) = \cos\pi = -1 \\ c_1 &=& \frac{1}{1!}\left.\frac{df}{dz}\right|_{z=z_0} = -\sin \pi = 0 \\ c_2 &=& \frac{1}{2!}\left.\frac{d^2f}{dz^2}\right|_{z=z_0} = -\frac{1}{2}\cos \pi = \frac{1}{2} \\ c_3 &=& \frac{1}{3!}\left.\frac{d^3f}{dz^3}\right|_{z=z_0} = \frac{1}{6}\sin \pi = 0 \\ c_4 &=& \frac{1}{4!}\left.\frac{d^4f}{dz^4}\right|_{z=z_0} = \frac{1}{24}\cos \pi = -\frac{1}{24} \\ \end{eqnarray*} (Don't forget the \(1/n!\).)

So, the approximation I end up with is:

\[ \cos z \approx -1 + \frac{1}{2} (z-\pi)^2 +-\frac{1}{24}(z-\pi)^4\]

This formula is the correct form of the power serie approximation. Do NOT multiply out and regroup the terms (do Not "FOIL") or you are undoing all the work you did to find the power series.

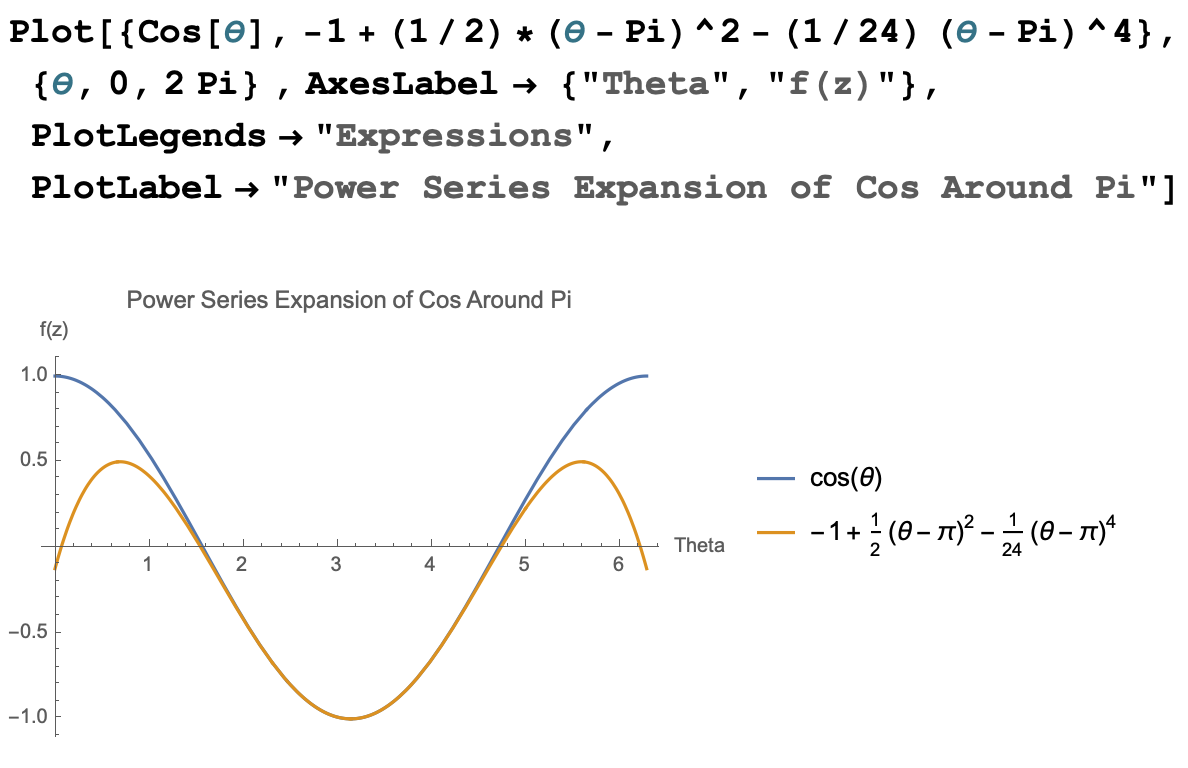

- Plot both the original function and your approximation.

Here is the code in Mathematica and the graph it produces.

- For what values of \(z\) is your approximation “good”?

When I plot this approximation against the cosine function, I see that the expansion approximates the cosine function reasonably well between about \(\pi/2\) and \(3\pi/2\). Inside this region, I can not even distinguish the graphs from each other. Beyond that region, the function and its approximation rapidly start to differ.

- Calculate the \(n=0, 1, 2, 3, 4\) coefficients of the power series for \(\cos{z}\) expanded around \(z=\pi\). Using these coefficients, find a power series approximation for this function.

- Series Notation 1

S1 5284S

Write out the first four nonzero terms in the series:

\[\sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty \frac{1}{n!}\]

\begin{eqnarray*} \sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty \frac{1}{n!} &=& \frac{1}{0!}+\frac{1}{1!}+\frac{1}{2!}+\frac{1}{3!}+...\\ &\approx&1 + 1 + \frac{1}{2} + \frac{1}{6} \end{eqnarray*} Note that \(0!=1\) by definition.

\[\sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n}{n!}\]

\begin{eqnarray*} \sum\limits_{n=1}^\infty \frac{(-1)^n}{n!} &=& \frac{(-1)^1}{1!}+\frac{(-1)^2}{2!}+\frac{(-1)^3}{3!}+\frac{(-1)^4}{4!}+...\\ &\approx& -1 + \frac{1}{2} - \frac{1}{6} + \frac{1}{24} \end{eqnarray*} Note that this series starts at \(n=1\).

- \begin{equation}

\sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty {(-2)^{n}\,\theta^{2n}}

\end{equation}

\begin{eqnarray*} \sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty {(-2)^{n}\,\theta^{2n}} &=&(-2)^0\theta^0+(-2)^1\theta^2+(-2)^2\theta^4+(-2)^3\theta^6+\,\dots\\ &\approx&1-2\theta^2+4\theta^4-8\theta^6 \end{eqnarray*}

- Series Notation 2

S1 5284S

Write (a good guess for) the following series using sigma \(\left(\sum\right)\) notation. (If you only know a few terms of a series, you don't know for sure how the series continues.)

\[1 - 2\,\theta^2 + 4\,\theta^4 - 8\,\theta^6 +\,\dots\]

\[\sum\limits_{n=0}^\infty {(-2)^{n}\,\theta^{2n}}\]

\[\frac14 - \frac19 + \frac{1}{16} - \frac{1}{25}+\,\dots\]

\[\sum\limits_{n=2}^\infty \frac{(-1)^{n}}{n^2}\]