Static Fields: Fall-2025

HW 02 (SOLUTION): Due W1 D5: Math Bits

- Find Area/Volume from the Vector Differential

S1 5280S

Start with \(d\vec{r}\) in rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinates. Use these expressions to write the scalar area elements \(dA\) (for different coordinate equals constant surfaces) and the volume element \(d\tau\). It might help you to think of the following surfaces: The various sides of a rectangular box, a finite cylinder with a top and a bottom, a half cylinder, and a hemisphere with both a curved and a flat side, and a cone.

-

Rectangular:

\begin{align}

dA&=\\

d\tau&=

\end{align}

\begin{align} dA&=\begin{cases}dx\, dy&\mbox{for \(z=\) const., ie. the top and bottom of a box.}\\ dy\, dz&\mbox{for \(x=\) const., i.e. the sides of a box.}\\ dz\, dx&\mbox{for \(y=\) const., ie. the sides of a box.}\\ \end{cases}\\ d\tau&=dx\,dy\,dz \end{align}

- Cylindrical:

\begin{align}

dA&=\\

d\tau&=

\end{align}

\begin{align} dA&=\begin{cases}sds\, d\phi&\mbox{for \(z=\) const., i.e. the top and bottom of a cylinder.}\\ sd\phi\, dz&\mbox{for \(s=\) const., ie. the curved sides of a cylinder.}\\ ds\, dz&\mbox{for \(\phi=\) const., ie. the flat part of a half cylinder.}\\ \end{cases}\\ d\tau&=s\,ds\,d\phi\,dz \end{align}

-

Spherical:

\begin{align}

dA&=\\

d\tau&=

\end{align}

\begin{align} dA&=\begin{cases}r^2\sin\theta\, d\theta\, d\phi&\mbox{for \(r=\) const., i.e. the surface of a sphere.}\\ r\sin\theta\, dr\, d\phi&\mbox{for \(\theta=\) const., i.e. the surface of a cone.}\\ r\, dr\, d\phi&\mbox{for \(\theta=\pi/2\), the flat bottom of a hemisphere.}\\ \end{cases}\\ d\tau&=r^2\sin\theta\,dr\,d\phi\,d\theta \end{align}

-

Rectangular:

\begin{align}

dA&=\\

d\tau&=

\end{align}

- Memorize the Vector Differential

S1 5280S

Write \(\vec{dr}\) in rectangular, cylindrical, and spherical coordinates.

-

Rectangular:

\begin{equation}

\vec{dr}=

\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \vec{dr}=dx\,\hat{x}+dy\,\hat{y}+dz\,\hat{z} \end{equation}

-

Cylindrical:

\begin{equation}

\vec{dr}=

\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \vec{dr}=ds\,\hat{s}+s\,d\phi\,\hat{\phi}+dz\,\hat{z} \end{equation}

-

Spherical:

\begin{equation}

\vec{dr}=

\end{equation}

\begin{equation} \vec{dr}=dr\,\hat{r}+r\,d\theta\,\hat{\theta}+r\,\sin\theta\,d\phi\,\hat{\phi} \end{equation}

-

Rectangular:

\begin{equation}

\vec{dr}=

\end{equation}

- Charge on a Spiral

S1 5280S

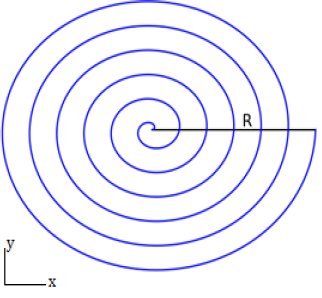

A charged spiral in the \(x,y\)-plane has 6 turns from the origin out to a maximum radius \(R\) , with \(\phi\) increasing proportionally to the distance from the center of the spiral. Charge is distributed on the spiral so that the charge density increases linearly as the radial distance from the center increases. At the center of the spiral the linear charge density is

\(0~\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}\). At the end of the spiral, the linear charge

density is \(13~\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}\). What is the total charge on the

spiral?

Let's start by finding the charge density on the spiral. We know that the charge density increases linearly with the distance from the center of the spiral, so our linear charge density will be proportional to the radius, \(s\). (Notice the two different uses of the word “linear”!) We also know that at the max radius, \(R\), we will have a linear charge density of \(13~\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}\), so we can solve for the proportionality constant, which we'll call \(\alpha\) \begin{align} \lambda(s) &= \alpha s\\ 13 ~\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}} &= \alpha R\\ \Rightarrow \alpha&=\frac{13~\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}}{R}\\ \lambda(s) &= \left(13~\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}\right) \frac{s}{R} \end{align}

Looking at our spiral:

We will chop up the spiral into little pieces and find the charge \(\lambda\, d\ell\) on each little piece. Then we will add up (integrate) the charge from each of the little pieces. (Sensemaking: Note that \(\lambda(s)\) has the correct units, since \(s/R\) is unitless---I will suppress the \(\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}\) and restore it at the very end.)

So the next thing we need to find is \(d\ell\) on a little piece of the spiral. \begin{align} d\ell&=\vert d\vec r\vert\nonumber\\ &=\vert ds\, \hat s + s d\phi\, \hat\phi + dz\, \hat z\vert\nonumber\\ &=\sqrt{ (ds\, \hat s + s\, d\phi\, \hat\phi)\cdot (ds\, \hat s + s\, d\phi\, \hat\phi) }\nonumber\\ &=\sqrt{ds^2 + s^2 d\phi^2} \end{align} We are trying to do a line integral, so we need to find \(d\ell\) in terms of a single parameter, but both \(\phi\) and \(s\) are changing. We need to know the relationship between \(\phi\) and \(s\) to proceed further. We were given the information that \(\phi\) will increase proportionally to the distance from the center of the spiral, which is the radius s, so we can write: \begin{align} s &= \beta \phi\\ \end{align} We also know that at the end of the spiral \(s=R\) and the spiral has to revolve 6 times around the center on its way there, so we know know \(\phi_{end} =6(2\pi)=12\pi\), and we can use this information to solve for \(\beta\): \begin{align} s &= \beta \phi\\ R &= 12\pi \beta \\ \Rightarrow\beta&=\frac{R}{12\pi}\\ s &=\frac{R}{12\pi} \phi\\ \end{align} Now, zapping this equation with \(d\), we get: \begin{align} ds &=\frac{R}{12\pi} d\phi\\ \end{align} We can plug the differential relationship into \(d\ell\), substituting for either \(ds\) or \(d\phi\). Since the charge density is written in terms of \(s\), it is a little simpler to eliminate \(d\phi\), using \(d\phi=\frac{12\pi}{R} ds\): \begin{align} d\ell&=\sqrt{ds^2 + s^2 d\phi^2}\nonumber\\ &=\sqrt{1 + s^2\left(\frac{12\pi}{R}\right)^2}~ds \end{align}

Putting all the pieces together and integrating with respect to \(s\), we have: \begin{align} Q &= \int_0^R \lambda(s)\, d\ell\nonumber\\ &=\int_0^R 13 \frac{s}{R} \sqrt{1 + s^2\left(\frac{12\pi}{R}\right)^2}~ds \end{align} We can integrate using substitution by letting \(u=1 + s^2\left(\frac{12\pi}{R}\right)^2\) and then zapping with \(d\) we get \(du= 2s\left(\frac{12\pi}{R}\right)^2 ds\) and so we have: \begin{align} Q &=\int_{u(0)}^{u(R)} 13 \frac{s}{R} \sqrt{u}~\frac{du}{2s\left(\frac{12\pi}{R}\right)^2}\nonumber\\ &=\int_{u(0)}^{u(R)} \frac{13R}{288\pi^2} \sqrt{u}~du\nonumber\\ &=\left[\frac{13R}{288\pi^2} \frac{2}{3} \left( 1 + s^2\left(\frac{12\pi}{R}\right)^2 \right)^\frac{3}{2}\right]_0^R\nonumber\\ &=\frac{13\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}~R}{432\pi^2} \left(\left( 1 + 144\pi^2 \right)^\frac{3}{2}-1\right)\nonumber\\ &\approx \left(163.53 \frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}\right)R \end{align} Sense-making: How can you be confident that an answer like this is correct? The dimensions work out (you can see that the square root is dimensionless, and the extra overall factor of \(R\) cancels the \(1/L\) in the units of the linear charge density, \(13~\frac{\textrm{C}}{\textrm{m}}\), to leave only Coulombs. We can also check limiting cases: If we let the radius of the spiral go to 0, we get \(Q=0\), which makes sense.. Similarly, if we let \(R\rightarrow \infty\) we see our charge becomes infinite, which should happen if we have an infinite spiral with a finite charge density.

- Cone Surface

S1 5280S

- Find \(dA\) on the surface of an (open) cone in both cylindrical and spherical coordinates. Hint: Be smart about how you coordinatize the cone.

In Cylindrical Coordinates:

Place the tip of the cone at the origin. Examining an infinitesimal element of the surface area of the cone, \(d\ell_1\) points along the surface of the cone straight out from the origin, while \(d\ell_2\) points in the \(\hat{\phi}\) direction. \begin{align} d\ell_1&=\sqrt{ds^2+dz^2} \\ d\ell_2&=sd\phi \end{align} We need to write \(d\ell_1\) in terms of a single variable, either \(s\) or \(\phi\), but not both. If the cone has height \(H\) and upper radius \(R\), then the opening angle of the cone implies that, for all points along the surface of the cone: \begin{align} z&=s\frac{H}{R} \\ dz&=ds\frac{H}{R} \end{align} where the coordinates range from \(s=0\) to \(s=R\) and from \(\phi=0\) to \(\phi=2\pi\). Therefore,

\begin{align} dA&=d\ell_1\, d\ell_2\\ &=\sqrt{ds^2+dz^2}\, sd\phi \\ &=\sqrt{1+\frac{H^2}{R^2}}ds\, sd\phi \\ \end{align}In Spherical coordinates:

\begin{align} d\ell_1&=dr \\ d\ell_2&=r\sin(\theta)d\phi \end{align} where \(\sin(\theta)=\frac{R}{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}}\) where \(\theta\) is the constant angle from the z-axis to the surface of the cone. Therefore

\begin{align} dA&=d\ell_1\, d\ell_2\\ &=dr\, r\sin(\theta)d\phi \\ &=\frac{R}{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}}\, r\, dr\, d\phi \end{align} - Using integration, find the surface area of an (open) cone with height \(H\) and radius \(R\). Do this problem in both cylindrical and spherical coordinates.

\begin{align} A_{cone}&=\int_{S_{cone}}dA \\ dA &= d\ell_1d\ell_2 \end{align}

In Cylindrical Coordinates:

Substituting \(dA\) and the limits of the coordinates into the integral above gives: \begin{align} A_{cone} &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{R} \sqrt{1+\frac{H^2}{R^2}} s\, ds\, d\phi \\ &=2\pi\, \frac{\sqrt{R^2+H^2}}{R}\, \int_0^{R} s\, ds \\ &=2\pi\, \frac{\sqrt{R^2+H^2}}{R}\frac{R^2}{2} \\ &=\pi R\sqrt{H^2+R^2} \end{align}

In Spherical coordinates:

We integrate first from \(r=0\) to \(r=\sqrt{H^2+R^2}\) and then from \(\phi=0\) to \(\phi=2\pi\). \begin{align} A_{cone} &=\int_0^{2\pi}\int_0^{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}}\frac{R}{\sqrt{H^2+R^2}}r\, dr\, d\phi \\ &=\frac{R\sqrt{H^2+R^2}}{2}\int_0^{2\pi}d\phi \\ &=\pi R\sqrt{H^2+R^2} \end{align} This is the same answer as we got using cylindrical coordinates! Cartesian coordinates can, of course, also be used, but because the limits of integration are complicated in Cartesian coordinates, it is tricky to get the answer using them. If the problem is round, including the limits, use round coordinates!

- Find \(dA\) on the surface of an (open) cone in both cylindrical and spherical coordinates. Hint: Be smart about how you coordinatize the cone.