Theoretical Mechanics: Fall-2025

HW 10 (SOLUTION): Due F 10/31 Day 28

- Bead on a Spinning Wire Hoop

S1 5334S

(modified from Taylor Ex. 7.6)

A small bead of mass \(m\) is threaded on a frictionless circular wire hoop of radius \(R\). The hoop lies in a vertical plane, which is forced to rotate about the hoop's vertical diameter with constant angular velocity \(\dot{\phi}=\omega\), as shown in Figure 7.9. The bead's position on the hoop is specified by the angle \(\theta\) measured up from vertical.

- Write down the Lagrangian for the system in terms of the generalized coordinate \(\theta\) and find \(\ddot{\theta}\). Discuss at least three strategies for making sense of your answer.

\begin{eqnarray*} KE = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 \end{eqnarray*}

Plugging in \(\vec{v}\cdot\vec{v}\):

\begin{eqnarray*} KE = \frac{1}{2}m(\dot{r}^2+r^2\dot{\theta}^2+r^2\dot{\phi}^2\sin^2\theta) \end{eqnarray*}

Acknowledging the constraints of this specific problem: \(r=R\) therefore \(\dot{r}=0\) and \(\dot{\phi} = \omega\):

\begin{eqnarray*} KE = \frac{1}{2}m(R^2\dot{\theta}^2+R^2\omega^2\sin^2\theta) \end{eqnarray*}

Using \(z=R\cos\theta\):

\begin{eqnarray*} PE = -mgR\cos\theta \end{eqnarray*}

Thus the Lagrangian is:

\begin{eqnarray*} \mathcal{L} = KE - PE = \frac{1}{2}m\left(R^2\dot{\theta}^2+R^2\omega^2\sin^2\theta\right) + mgR\cos\theta \end{eqnarray*}

Applying the Euler-Lagrange Equations for the variable \(\theta\).

\begin{eqnarray*} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta}=\frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{\theta}}\\ mR^2\omega^2\sin\theta \cos\theta-mgR\sin\theta = mR^2\ddot{\theta}\\ \rightarrow \ddot{\theta}=\omega^2\sin\theta \cos\theta - \frac{g\sin\theta}{R} \end{eqnarray*}

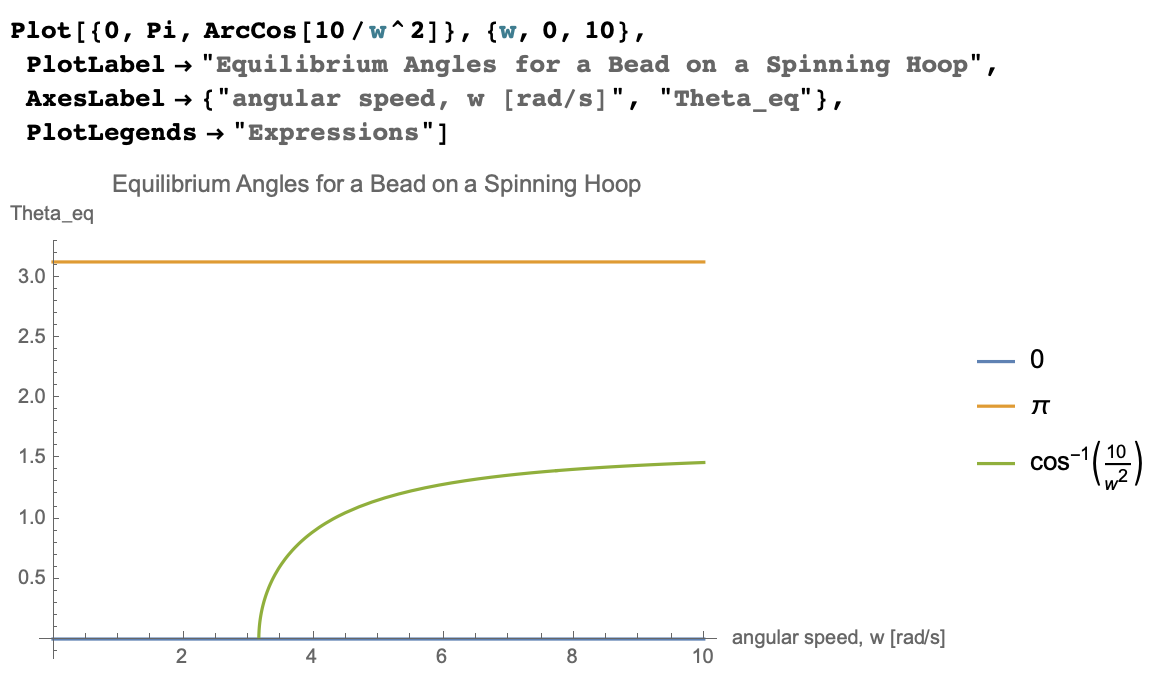

- Find the angles for which \(\ddot{\theta} = 0\) - these are equilibrium angles. Show these locations on a sketch of the hoop. Use at last three strategies for making sense of your answer. Include and discuss a plot the equilibrium angles vs. \(\omega\)

\begin{eqnarray*} 0= \omega^2\sin\theta_{eq} \cos\theta_{eq} - \frac{g\sin\theta_{eq}}{R}\\ = \sin\theta_{eq}\left(\omega^2 \cos\theta_{eq} - \frac{g}{R}\right) \end{eqnarray*}

This equation is true if:

- \(\sin\theta_{eq}=0\) for \(\theta_{eq}=0,\pi\)

- \(0=\omega^2 \cos\theta_{eq} - \frac{g}{R}\) so \(\theta_{eq}=\arccos\left( \frac{g}{R\omega^2}\right)\)

Sensemaking:

Check Dimensions:

The argument of arccos should be dimensionless: \(\frac{g}{R\omega^2} = \frac{L/T^2}{L(1/T^2)}=\)dimensionless. Yay!

Check a Special Case: Spinning really fast.

My intuition is that if the ring is spinning really fast, then the equilibrium angle of the bead should be \(\pi/2\) (because of “centrifugal” force):

If \(\omega \rightarrow \infty\), then the equilibrium angle \(\theta_{eq} = \arccos(0) = \pi/2\) Yay!

Check a Special Case: The ring is not spinning

My intuition is that the slower the ring rotates, the equilibrium angle that depends on the spin rate will go to zero:

\(\cos\theta_{eq} = \frac{g}{R\omega^2} \rightarrow \infty\)

This never happens, so I need to be more careful is checking this case by plotting the function:

This plot tells me that the \(\omega\)-dependent equilibrium angle doesn't occur until \(\omega^2=g/R\). Therefore, I need to refine my intuition a bit - this equilibrium angle doesn't exist until the hoop is spinning sufficiently fast. The smaller the hoop, the larger this angular speed is.

- \(\sin\theta_{eq}=0\) for \(\theta_{eq}=0,\pi\)

- Write down the Lagrangian for the system in terms of the generalized coordinate \(\theta\) and find \(\ddot{\theta}\). Discuss at least three strategies for making sense of your answer.

- A Ball Confined to the Surface of a Sphere in Near-Earth Gravity

S1 5334S

A ball with mass \(m\) is confined to move on

the surface of a sphere with radius \(r=R\). A convenient choice of coordinates is

spherical, \(r\), \(\theta\), \(\phi\), with the polar axis pointing straight down. (Remember: in physics, \(\phi\) is the azimuthal angle in the \(xy\)-plane and \(\theta\) is the angle with the \(z\)-axis.)

-

Find the equations of motion using a Lagrangian approach. Use at least three

sense-making strategies to evaluate each equation.

\begin{equation*} KE = \frac{1}{2}mv^2 \end{equation*} Plugging in \(\vec{v}\cdot\vec{v}\) in spherical coordinate (physics version): \begin{equation*} KE = \frac{1}{2}m(\dot{r}^2+r^2\dot{\phi}^2\sin^2\theta+r^2\dot{\theta}^2) \end{equation*} Acknowledging the constraints of this specific problem: \(r=R \Rightarrow\dot{r}=0\) \begin{equation*} KE = \frac{1}{2}m(R^2\dot{\phi}^2\sin^2\theta+R^2\dot{\theta}^2) \end{equation*} Using \(z=R\cos\theta\) from problem 1 part a. \begin{equation*} PE = -mgR\cos\theta \end{equation*} Thus the Lagrangian is: \begin{equation*} \mathcal{L} = KE - PE = \frac{1}{2}m\left(R^2\dot{\phi}^2\sin^2\theta+R^2\dot{\theta}^2\right) + mgR\cos\theta \end{equation*} Applying the Euler-Lagrange Equations for the two variables, \(\phi\) and \(\theta\). \begin{align*} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \phi}&=\frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{\phi}}\\ 0 &= \frac{d}{dt}\left(mR^2\sin^2\theta\dot{\phi}\right)\\ 0 &= mR^2\left(2\sin\theta\cos\theta\dot{\theta}\dot{\phi}+\sin^2\theta \ddot{\phi}\right)\\ \Rightarrow \ddot{\phi} &= -2\cot\theta\dot{\theta}\dot{\phi}\\ \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \theta}&=\frac{d}{dt}\frac{\partial \mathcal{L}}{\partial \dot{\theta}}\\ mR^2\dot{\phi}^2\sin\theta \cos\theta-mgR\sin\theta &= mR^2\ddot{\theta}\\ \Rightarrow \ddot{\theta} &=\dot{\phi}^2\sin\theta \cos\theta - \frac{g\sin\theta}{R} \end{align*}

Sensemaking:

Check Dimensions:

\begin{align*} \ddot{\phi} = -2\cot\theta\dot{\theta}\dot{\phi} \rightarrow& \Big[\frac{1}{T^2} \Big] = \Big[ \frac{1}{T}\Big] \Big[ \frac{1}{T}\Big] \\ &\Big[\frac{1}{T^2} \Big] = \Big[ \frac{1}{T^2}\Big] Yay!\\[12pt] \end{align*}

\begin{align*} \ddot{\theta} =\dot{\phi}^2\sin\theta \cos\theta - \frac{g\sin\theta}{R} \rightarrow& \Big[\frac{1}{T^2} \Big] = \Big[ \frac{1}{T}\Big]^2 - \frac{[\cancel{L}/T^2]}{\cancel{L}} \\ &\Big[\frac{1}{T^2} \Big] = \Big[ \frac{1}{T^2}\Big] \quad \mbox{Yay!}\\[12pt] \end{align*}

Check Special Cases:

\(\phi = constant\) or \(\dot{\phi}=0\)

Expectation: I should get the equation of motion for a pendlulum: \(\ddot{\theta} = -\frac{g}{R}\sin\theta\) and no acceleration in the azimuthal direction \(\ddot{\phi} = 0\)

Check:

\begin{align*} \ddot{\theta} =(0)\sin\theta \cos\theta - \frac{g\sin\theta}{R} = \frac{g\sin\theta}{R}\quad \mbox{Yay!}\\[6pt] \ddot{\phi} = -2\cot\theta\dot{\theta}(0) = 0 \quad \mbox{Yay!}\\ \end{align*}

Functional Behavior:

This is a really tough one. These 2nd order ordinary differential equations are coupled and there is no easy way to decouple them. One thing I do notice is that the functions are trigonometric, which makes sense for circles/spheres.

The first term of the \(\ddot{\theta}\) acceleration (polar acceleration) gets more positive (flares up) as \(\dot{\phi}\) increases, which makes intuitive sense with centrifugal acceleration. The second term makes the \(\ddot{\theta}\) acceleration more negative (gets pulled down) by gravity which I expect from gravity.

-

Explain what the \(\phi\) equation indicates about the \(z\)-component of angular

momentum.

Due the right hand rule the \(z\)-component of the angular momentum is the momentum that is conjugate to the coordinate \(\phi\). In other words, \(L_z = \partial \mathcal{L}/ \partial \dot{\phi}\). The Lagrangian does not depend on the coordinate \(\phi\) (even though it does depend on \(\dot{\phi}\)), so the \(z\)-component of angular momentum \(L_z\) is conserved. In other words, since:

\begin{align} \frac{\partial\mathcal{L}}{\partial\phi}&=\frac{d}{dt}\left(\frac{\partial\mathcal{L}}{\partial\dot{\phi}}\right)\\ 0&=\frac{d}{dt} L_z \\ \Rightarrow L_z &= constant\\ \end{align}

-

Discuss the specific special case that \(\phi = \) constant. What does the equation of motion for \(\theta\) indicate?

If \(\phi =\) constant, then the motion is constrained to a vertical plane, and I expect the equations of motion to be the same as a plane pendulum. If \(\phi =\) constant then \(\dot{\phi}=0\) thus \(\ddot{\theta}=-\frac{g\sin\theta}{R}\) which is the angular acceleration of a plane pendulum!

-

Find the equations of motion using a Lagrangian approach. Use at least three

sense-making strategies to evaluate each equation.