Theoretical Mechanics: Fall-2025

HW 3 (SOLUTION): Due W 10/8 Day 11

- Constant Acceleration by Separation of Variables

S1 5316S

Calculate: Treat Newton's 2nd law as a separable differential equation and solve for the velocity and position as a function of time of an object that is all of the following:

- moving in one dimension,

- not initially at the origin of coordinates,

- moving with a non-zero initial speed,

- experiences a constant force.

I'll start with Newton's Second Law:

\begin{eqnarray*} \Sigma \vec{F} = m\vec{a} = m \frac{d\vec{v}}{dt} \end{eqnarray*} Since there is only one, constant force (\(C\)), set the mass times acceleration equal to a constant. \begin{eqnarray*} \Sigma \vec{F} = C\\ \therefore C = m\frac{dv}{dt} \end{eqnarray*} This equation is separable, so I'll separate time and velocity and integrate each side. \begin{eqnarray*} C dt = mdv\\ \int_{0}^{t} C dt' = \int_{v_0}^{v}mdv' \\ Ct'\Bigr|_{0}^{t} = mv' \Bigr|_{v_0}^{v}\\ C(t-0) = m(v-v_0)\\ v(t)=\frac{C}{m}t+v_0 \end{eqnarray*} Note carefully that I introduced many new constants in the calculation above. I used the principle to "name the things you don't know" so that you can put these names (typically algebraic symbols) into equations. I have named the initial time zero, the final time \(t\), the initial velocity \(v_0\), and the final velocity \(v\). When I integrated both sides of the equation in the second line, I recognized that the I was integrating with respect to time on the left, so the limits of integration that I used were the inital time to the final time. On the right-hand side, I recognized that I was integrating with respect to velocity, so the limits of integration that I used were the initial and final velocities.

To find the position, I'll integrate again. I recognize that \(v\) is \(\frac{dx}{dt}\). \begin{eqnarray*} \frac{dx}{dt}=\frac{C}{m}t+v_0 \end{eqnarray*} Again, this equation is separable and I'll separate of position and time and integrate each side. \begin{eqnarray*} dx=\Bigr(\frac{C}{m}t+v_0\Bigr)dt\\ \int_{x_0}^{x}dx'=\int_{0}^{t}\Bigr(\frac{C}{m}t'+v_0\Bigr)dt'\\ x'\Biggr|_{x_0}^{x}=\Bigr(\frac{C}{m}\frac{t'^2}{2}+v_0t'\Bigr)\Biggr|_{0}^{t}\\ x-x_0=\frac{1}{2}\frac{C}{m}t^2+v_0t\\ x(t)=\frac{1}{2}\frac{C}{m}t^2+v_0t+x_0 \end{eqnarray*} Here I have introduced symbols for the initial position \(x_0\) and the final position \(x\).

Reflect: Do your answers look familiar? If yes, from where? If not, how would you have to modify these equations to be similar to equations you know?

\(C/m\) is a constant acceleration. Substituting \(C/m=a\), I get: \begin{eqnarray*} v(t)=at+v_0 \\ x(t) = \frac{1}{2}at^2+v_0t+x_0 \end{eqnarray*} These are the kinematic equations I learned in introductory physics.

- Separable ODE linear + constant

S1 5316S

Solve the differential equation:

\(\frac{dv}{dt}=-b-cv\) where \(v(t=0)=v_0\)

First, I recognize this as a separable differential equation, so I'll separate and integrate both sies. I'll use definite integrals, paying special attention to the limits.

The lower limit, on each side should correspond to the same state of the system, and the same should be true of the upper limit, but on the left I'll have a velocity component and on the right I'll have the corresponding time.

\begin{align*} \frac{dv}{b+cv} &= -dt\\ \int_{v_0}^v \frac{dv'}{b+cv'} &= -\int_0^t dk'\\ \end{align*}

To perform the integral on the left, I need to integrate by substitution.

\begin{align*} \mbox{let }u &= b+cv\\ du &= cdv\\ \end{align*}

Now, I'll reformulate the integral, and I'll pay special attention to the limits of integration.

\begin{align*} \int_{b+cv_0}^{b+cv}\frac{1}{c} \frac{du}{u} &= -\int_0^t dt'\\ \ln{u}\bigg|_{b+cv_0}^{b+cv} &= -ct\\ \ln(b+cv)-\ln(b+cv_0) &= -ct \\ \end{align*}

At this stage I'm concerned that I might be taking the log of a quantity with dimensions. I'll make use of the properties of logs to make the argument dimensionless.

\begin{align*} \ln{\left(\frac{b+cv}{b+cv_0}\right)} &= -ct \\ \end{align*}

The last step is to solve for \(v(t)\) by exponentiating both sides.

\begin{align*} v(t) &=\left(\frac{b}{c}+v_0\right)\;e^{-ct}-\frac{b}{c} \end{align*}

To check this, I'll first think about the dimensions of all the variables:

- \(b\) must have the same dimensions as \(v\)/\(t\)

- \(c\) must have the same dimensions as \(1/t\)

Plugging the dimensions in (using brackets to remind myself that these are dimensions, not the actual variables):

\begin{align*} [v] &= \Big(\frac{[v]/\cancel{[t]}}{1/\cancel{[t]}} + [v] \Big) e^{(1/\cancel{[t]})\cancel{[t]}} - \frac{[v]/\cancel{[t]}}{1/\cancel{[t]}} \\ [v] &= \Big([v] + [v] \Big) e^{\text{dimensionless}} +[v] \end{align*}

All the terms have dimensions of [v] so the dimensions balance across the equals sign.

I can also check by taking the derivative of both side and recognizing that I get the original differential equation back:

\begin{align*} \frac{dv}{dt} &=-c\left(\frac{b}{c}+v_0\right)\;e^{-ct} \\ &= -c\Big( v(t) + \frac{b}{c} \Big)\\ &= -cv-b \quad \checkmark \end{align*}

- Distance Formula in Curvilinear Coordinates

S1 5316S

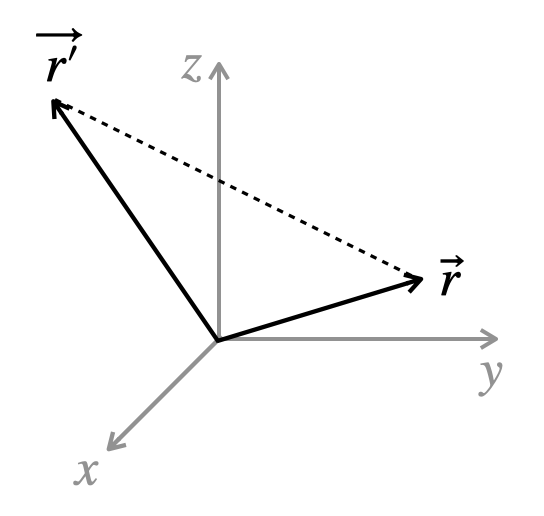

The distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\) and the point \(\vec r'\) is a coordinate-independent, physical and geometric quantity. But, in practice, you will need to know how to express this quantity in different coordinate systems.

Find the distance \(\left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert\) between the point \(\vec r\) and the point \(\vec r'\) in rectangular coordinates.

In rectangular coordinates: \begin{align} \left| \vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \left|(x\hat{x}+y\hat{y}+z\hat{z}) -(x\,{}'\hat{x}+y\,{}'\hat{y}+z\,{}'\hat{z})\right|\\ &= \left|((x-x')\hat{x}+(y-y')\hat{y}+(z-z')\hat{z}) \right|\\ &= \sqrt{((x-x')\hat{x}+(y-y')\hat{y}+(z-z')\hat{z}) \cdot ((x-x')\hat{x}+(y-y')\hat{y}+(z-z')\hat{z})}\\ &= \sqrt{(x-x\,{}')^2+(y-y\,{}')^2+(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{align}

Sense-making: This is the Pythagorean Theorem!

Show that this same distance written in cylindrical coordinates is: \begin{equation*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| =\sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{equation*}

Hint: You may want to use the textbook: GMM: Change of Coordinates

In cylindrical coordinates: \begin{align*} x &= s\cos\phi\\ y &= s\sin\phi\\ z &= z \end{align*} Plug these coordinates into the ANSWER to the first part, above. Then simplify using appropriate trig identities including an addition formula. Now would be a good time to learn how to find the trig identities quickly online or in a reference book.

(Note: You might be tempted to do this calculation by starting with an expression for the position vector using both cylindrical coordinates and cylindrical basis vectors. This strategy is impossible because the cylindrical basis vectors at \(\vec r\) and \(\vec r'\) are different from each other, so you cannot subtract these vectors without resorting to fancy differential geometry/general relativity! If you don't yet know about cylindrical basis vectors, ignore this comment for now.)

\begin{align*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \sqrt{(s\cos\phi-s\,{}'\cos\phi\,{}')^2 +(s\sin\phi-s\,{}'\sin\phi\,{}')^2 + (z-z\,{}')^2}\\ &= \left[s^2(\cos^2\phi+\sin^2\phi) +s\,{}'^2(\cos^2\phi\,{}'+\sin^2\phi\,{}')\right.\\ &~~~\left. -2s\,{}' s(\cos\phi\cos\phi\,{}'+\sin\phi\sin\phi\,{}') +(z-z\,{}')^2\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}\\ &= \sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')+(z-z\,{}')^2} \end{align*}

Show that this same distance written in spherical coordinates is: \begin{equation*} \left\vert\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right\vert =\sqrt{r'^2+r\,{}^2-2rr\,{}' \left[\sin\theta\sin\theta\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}'\right]} \end{equation*}

Hint: You may want to use the textbook: GMM: Change of Coordinates

In spherical coordinates: \begin{align*} x &= r\sin\theta \cos\phi\\ y &= r\sin\theta \sin\phi\\ z &= r\cos\theta \end{align*} Plug these coordinates into the ANSWER to the first part, above. Also, see the notes in the solution to the cylindrical case. \begin{align*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| &= \left[(r\sin\theta \cos\phi-r\,{}'\sin\theta\,{}'\cos\phi\,{}')^2\right.\\ &~~\left. +(r\sin\theta\sin\phi -r\,{}'\sin\theta\,{}' \sin\phi\,{}')^2\right.\\ &~~\left. +(r\cos\theta -r\,{}'\cos\theta\,{}')^2\right]^{\frac{1}{2}}\\ &= \left\{ r^2 [\sin^2\theta(\cos^2\phi +\sin^2\phi)+\cos^2\theta]\right.\\ &~~\left. +r\,{}'^2 [\sin^2\theta\,{}'(\cos^2\phi\,{}'+\sin^2\phi\,{}') +\cos^2\theta\,{}' ]\right.\\ &~~\left. -2rr\,{}'[\sin\theta \sin\theta\,{}'(\cos\phi\cos\phi\,{}' +\sin\phi\sin\phi\,{}')+\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}']\right\} ^{\frac{1}{ 2}}\\ &=\sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}'[\sin\theta \sin\theta\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}') +\cos\theta\cos\theta\,{}']} \end{align*}

Sense-making: Wow, that is an ugly expression (don't memorize this one, by the way). Let's try some special cases. If \(\phi = \phi\,{}'\), we can use a trig identity to reduce the distance formula to \begin{equation*} \left|\vec r -\vec r\,{}'\right| = \sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}' \cos\left(\theta - \theta\,{}'\right)} \end{equation*}

This is the law of cosines, which makes sense because you can easily write the angle between the two vectors in terms of the difference in the polar angles \(\theta\). The same trick doesn't work the same way for \(\theta = \theta\,{}'\), since the difference in \(\phi\) is not the difference in angles---unless \(\theta = \theta\,{}' = \pi/2\), which is on the equator (see next part).

-

Now assume that \(\vec r\,{}'\) and \(\vec r\) are in the \(x\)-\(y\) plane. Simplify

the previous two formulas.

Cylindrical Coordinates at \(z=0\) and \(z\,{}'=0\) \begin{equation*} \sqrt{s^2+s\,{}'^2-2ss\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')} \end{equation*}

Spherical Coordinates at \(\theta\,{}'=\frac{\pi}{2}\Rightarrow \cos\theta\,{}'=0\) and \(\sin\theta\,{}'=1\). (Also true for \(\theta\).) \begin{equation*} \sqrt{r^2+r\,{}'^2-2rr\,{}'\cos(\phi-\phi\,{}')} \end{equation*}

Behold the Law of Cosines once again!