Contemporary Challenges: Spring-2021

Homework 7 : Due 24 Friday

- Flute and boundary conditions

S0 4195S

Adapted from Q2M.1 from Chpt 2 of Unit Q, 3rd Edition

Waves of pressure (sound waves) can travel through air. When there are boundary conditions on a sound wave, the allowed frequencies become discretized (i.e. there is a discrete set of possible values). The same thing happens in quantum mechanics with "matter waves". Before getting fully into quantum mechanics, I want to warm up with musical examples. The PDE for pressure waves in a column of air is \begin{align} \frac{\partial^2p}{\partial t^2}=v_\text{s}^2\frac{\partial^2p}{\partial x^2} \end{align} where \(p\) is the pressure at time \(t\) and position \(x\), and \(v_\text{s}\) is a constant called the the speed of sound in air. We will look for solutions of the form \(p(x,t) = \sin(kx)\cos(wt) + \text{constant}\). The pressure at the open end of a pipe is fixed at 1 atmosphere (this boundary condition is called a node, because pressure doesn't fluctuate). If a pipe has a closed end (which may or may not be true for a flute) the pressure at the closed end can fluctuate up and down (this boundary condition would be called an anti-node).

- A concert flute, shown above, is about 2 ft long. Its lowest pitch is middle C (about 262 Hz). On the basis of this evidence, should we consider a flute to be a pipe that is open at both ends, or at just one end? Support your argument with a quantitative comparison. (The end of the flute farthest from the mouth piece is clearly open. The other end of the flute seems to be closed, so if you claim that the flute is open at both ends, you should try to explain where the other open end is.)

- What are the lowest three frequencies that can be played on a flute when all the finger holes are closed? Give you answer in units of Hz. Draw these frequencies on a spectrogram (vertical axis represents frequency, horizontal axis is time). Multiple horizonal lines at the same time represent the superposition of multiple frequencies.

- Not graded this year - think about this question if you are interested: The orchestra is warming up their instruments. The air in the flute starts at 290 K and increases temperature to 300 K. How seriously does this affect the pitch of the flute? For reference, each step on a chromatic musical scale has a frequency 1.06 times higher than the one below it (1.06 = \(2^{1/12}\)). The conductor of the orchestra will be upset if the flute shifts from its correct frequency by \(\pm 1\%\). The speed of sound in a gas is \(v_s= \sqrt{(\gamma P_0/\rho_0)}\) where \(\gamma\) is a dimensionless constant, \(P_0\) is the ambient pressure and \(\rho_0\) is the gas's density. As the gas warms up, the density of air inside the flute drops (the equilibrium air pressure inside the flute does not change).

- Cosmic Background Radiation

S0 4195S

The universe is filled with thermal radiation that has a blackbody spectrum at an effective temperature of 2.7 K. What is the wavelength of light that corresponds to the peak in \(S_\lambda\) (\(S_\lambda\) is the spectral distribution with respect to wavelength)? In what region of the electromagnetic spectrum is this peak wavelength?

- Reentry Heating of the Space Shuttle

S0 4195S

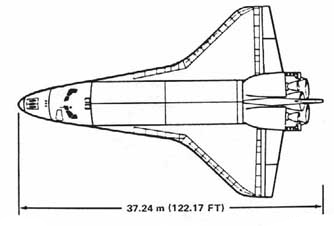

When NASA's Space Shuttle Orbiter descends from orbit it must pass through the upper reaches of Earth's atmosphere where the air is extremely thin. In this upper atmosphere, air molecules collide with the space shuttle and cause significant heating (transfer of kinetic energy). At very high altitudes, there aren't enough air molecules for convective heat transport. At these altitudes, the primary mechanism for cooling the Orbiter is the emission of blackbody radiation.

The Orbiter has a heat shield on its underside (see the black panels in the photo at the bottom of the page). This heat shield reaches a temperature of 2000 K. The topside of the Orbiter stays cool (\(\approx\) 300 K).

Estimate the maximum rate of decent of the shuttle through the upper atmosphere (the decrease in elevation per unit time). The primary constraint is that the temperature of the heat shield cannot safely exceed 2000 K (glowing red hot). This estimate will require a few steps:

At what rate is blackbody radiation emitted from the Orbiter's heat shield when its underside reaches a temperature of 2000 K? Give your answer in J/s.

Note: the space shuttle is about 35 m long, and has a wingspan (from wingtip to wingtip) of 25 m.

The Orbiter has a velocity component parallel to the Earth's surface, \(v_\parallel\), and a velocity component pointing toward the Earth's surface, \(v_\perp\). To build physical intuition about the descent, let's use reasoning and simple modeling to test some hypotheses about the dominant energy transformations involved. As a first hypothesis, we'll consider a plausible coarse-grained model: assume the Orbiter's total kinetic energy remains constant during reentry, while its gravitational potential energy decreases. Apply the First Law of Thermodynamics (conservation of energy) to estimate the maximum value of \(v_\perp\). Express your answer in units of m/s.

Note: Gravitational potential energy is changing, and electromagnetic radiation energy is being generated. The orbiter's mass is about 80,000 kg, similar to the mass of 80 cars.

Now try analyzing the descent again, this time accounting for the changing kinetic energy of the Orbiter. Use the following information to construct a plausible coarse-grained model. As before, we're using physical reasoning to test hypotheses about the descent, but now incorporating additional detail to better reflect the energy transformations involved. Our goal is to estimate the time required for a safe descent:

Time of ignition for the de-orbit burn is about 60 minutes before landing. The burn lasts 3 to 4 minutes and slows the Orbiter enough to begin its descent. About 30 minutes before landing, the Orbiter begins to encounter the effects of the upper atmosphere and the heat shields start to heat up. This usually occurs at an altitude of about 130 km, more than 8,000 km from the landing site. At this point, the Orbiter is traveling at 7500 m/s relative to the atmosphere. Around 15 minutes before landing, it has descended to an altitude of about 10 km (comparable to the cruising altitude of commercial aircraft) and is traveling at approximately the speed of sound (340 m/s).

Using this new information about changes in velocity and altitude, estimate the time required for “braking with fire” (the hot and fiery segment of the descent). Compare to the actual timeline. What physical mechanisms are still missing from the coarse-grained model of the fiery descent? What would be a sensible next level of model refinement?

- Spectra

S0 4195S

-

based on Q11M.2

Suppose an electron is trapped in a box whose length is \(L= 1.2 \text{ nm}\). The energy levels for this electron are \begin{align} E = \frac{h^2 n^2}{8 m L^2} \end{align} where \(m\) is the mass of the electron and \(n= 1,\ 2,\ 3,\ ...\) Draw a spectrum chart (like figure Q11.2) showing all the visiblelight emission lines from this system. \(\Delta n\) can be any odd integer. -

based on Q11B.5

Find the wavelength of the photon emitted during a \(n= 5\rightarrow4\) transition in a hydrogen atom.

Note: The energy levels in a hydrogen atom are \begin{align} E_n = \frac{-13.6 \text{ eV}}{n^2} \end{align} where \(n = 1,\ 2,\ 3,\ ...\) - Suppose a charge is held in position by an electrostatic spring (i.e. the restoring force on the charge follows Hooke's law, \(F= -kx\)). The mass of the charge, and the spring constant, are such that the system has a natural frequency \(\omega = 1016\text{ rad/s}\). Find the wavelength of the photon emitted during a \(n= 1 \rightarrow 0\) transition.

The quantum energy levels of a harmonic oscillator are \begin{align} E_n = \hbar \omega (n + \frac{1}{2}) \end{align} where \(n= 0,\ 1,\ 2,\ ...\)

Sense making: Try approaching this question from a classical physics perspective. What wavelength of light would we expect from a charge that oscillates at \(\omega = 10^{16} \text{ rad/s}\)?

-

based on Q11M.2

- Light emitting diodes

S0 4195S

To make blue light emitting diodes (LEDs), technology companies combine the elements indium, gallium and nitrogen in the correct ratio to make InGaN crystals. The figure above shows a small InGaN crystal. To make red LEDs, technology companies combine aluminum, gallium and arsenide in the correct ratio to make AlGaAs crystals.

InGaN and AlGaAs crystals are both semiconductors (see Q11.6). In a semiconductor, there are quantum states with relatively low energy that are almost fully occupied by electrons. Additionally, there are quantum states at higher energies that are not usually occupied by electrons. The energy gap between the low-energy and high-energy quantum states is called the “band gap”. To operate an LED, a battery injects electrons into the high-energy states. These injected electrons then fall into low-energy states and release photons. The size of the energy jump determines the color of light that is emitted.

(a) Estimate the size of the energy gap in InGaN. Give your answer in eV or joules.

(b)Estimate the size of the energy gap in AlGaAs. Give your answer in eV or joules.